Gillian Flynn’s unreliable narrators, Amy Dunne, Camille Preaker, and Libby Day, are anything but perfect. If you’ve read Flynn, you know the bestselling American novelist’s recipe: female leads from dysfunctional or broken families with mentally unstable parental figures. These women are troubled, damaged, and often harbour deep, dark secrets that lead them to even murder.

In a world where our social media feeds have embraced terms such as coquette, tradwife, or even the I’m just a girl trend, Flynn’s portrayal of unstable women with violent tendencies is stimulating. Her characters are not soft, traditional, nor innocent and don’t pretend to be. Perhaps that is why their flaws feel almost comforting.

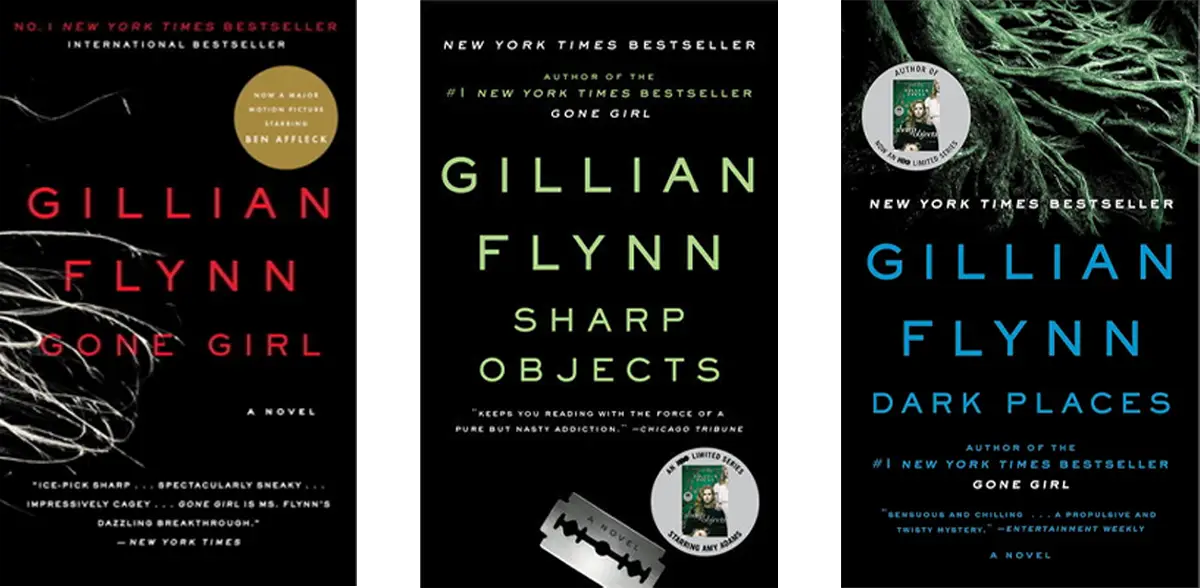

The protagonists of all three of Flynn’s novels, Sharp Objects (2006), Dark Places (2009), and Gone Girl (2012), suffer from a damaged notion of reality. Forever framed by their trauma, their crooked vision of the world is the fault of other people’s poor decisions. Utterly alone in their experience, they carry emotional baggage that leads them to feel as if they have no one to ask for help. Which leaves me wondering: Can we become hostages of our past and trauma? Are we forever the same children we once were? We cannot really blame Camille, Libby and Amy for all the internalized damage they face day in and day out, can we?

One thing is for sure: we all carry pain.

Society has invented all sorts of different names for the type of woman Flynn describes: witch, whore, crazy, hysterical. Whilst the author never falls into that trap, she doesn’t excuse her characters’ questionable decisions either. The truth is, these women are full of rage, sadness, and loneliness; some of them have even been abused during their childhoods. In Sharp Objects, protagonist Camille Preaker’s mother, Adora Crellin, captures this darkness: “Sometimes I think illness sits inside every woman, waiting for the right moment to bloom.”

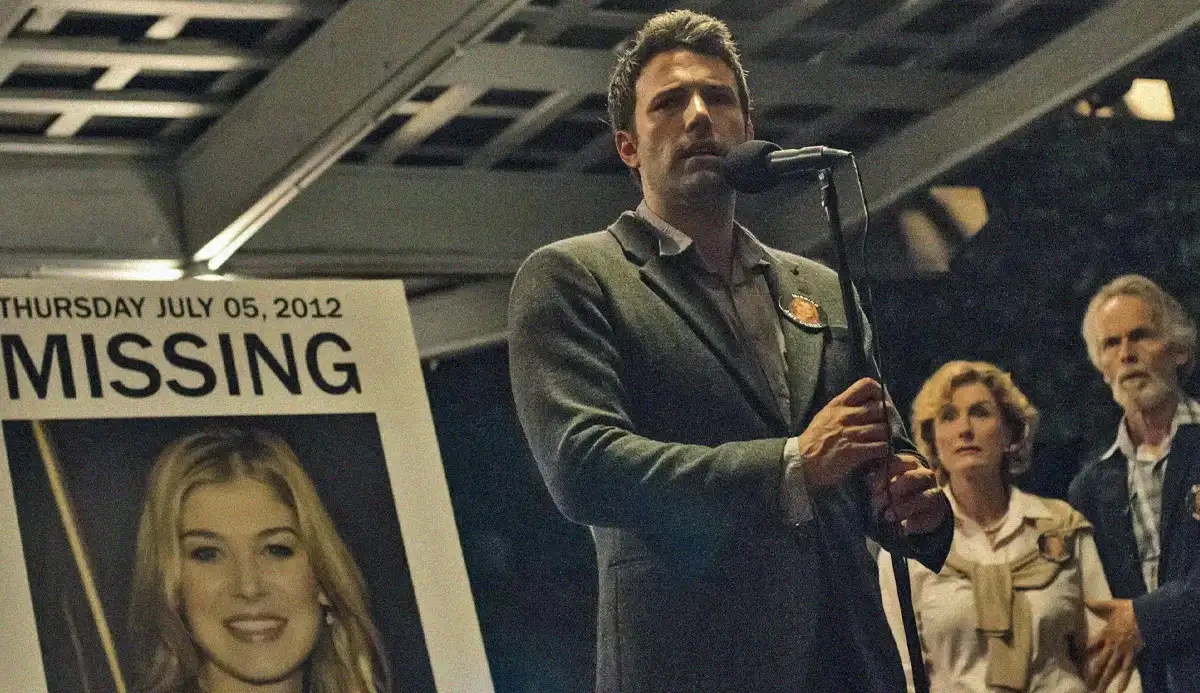

Such feelings of despair have been bottled up for years in each character’s inner world. They don’t commit premeditated murders because they never plan the murder itself. When the moment arrives, they kill because the fear of abandonment is too great to handle. Sometimes, the resulting death is an accident. We have different examples; from Adora Crellin (Sharp Objects) causing sickness to her daughters to feel loved and needed, to Amy Dunne (Gone Girl) incriminating her own husband of murdering her so she could get back the power she felt lost long ago in her marriage, and even Diondra Wertzner (Dark Places) manipulating a potential incel (Ben Day) into murder in order to feel she was in charge of her own survival.

Perhaps the reason why Flynn’s novels have grown such a cult following is because they present an uncomfortable truth: women, too, are capable of murder. Whereas our culture has always imagined murder as a man’s domain, the American author subverts this thinking, presenting women not playing the victim’s role but the aggressor’s. Flynn is brave enough to face the darkest aspects of womanhood with vulnerability and realism.

Amid the conservatism sweeping the Western political and cultural climate, women are once again being corralled into the roles of mother, daughter, and wife. Flynn, however, demonstrates that women in traditional female roles are more than capable of becoming perpetrators of the worst crimes. Her novels reflect the difficulty of living up to the expectations of conventional female roles, exploring the feelings of entrapment that can arise from them and the psychological damage that subsequently surfaces. Munchausen syndrome, addictions, anxiety, self-harm, multipersonality disorder, and depression are merely a few of the many disorders and illnesses covered in the pages of these books.

Women have traditionally been understood as caregivers, watching over their husbands, children, and parents. We have cooked, cleaned, and tidied the home for the family’s benefit. From a simplistic point of view, we could argue that women were the backbone of the family’s success. From a wider perspective, we could dispute that society could have stopped spinning without women’s work enabling men to pursue careers and jobs outside the household.

The concept of a female killer is shocking to our culture because it challenges the caregiver figure. In every way, shape, and form, it contradicts the portrait of the nurturing mother who feeds you when you are a child, challenging the idea of the daughter who sacrifices her personal life to devote herself to her parents, and clashes with the figure of the wife who will stay by his husband’s side no matter what. Flynn’s protagonists could break with the generational trauma and the people who hurt them by taking some distance and starting a new life. Instead, they choose to embrace their rage and react. In a way, you can’t blame them.

Flynn’s characters reject being what she refers to in Gone Girl as the ‘cool girl’—the woman who changes herself to appease the male gaze and be seen as lovable or respected in the eyes of men. In an interview, Flynn explained, ‘to pretend to be today’s ‘Cool Girl’ is just as restrictive and confining as it was for women back in the 1950s who were forced into the ‘Happy Homemaker’ role.’ We stopped being cool girls a long time ago. Let’s remember that.

Don’t get me wrong, Gillian Flynn doesn’t excuse murder perpetrated by women, nor do I, for that matter. But it’s certainly interesting to consider how the realities that generate most of the discomfort for women are the very ones that contradict the patriarchal status quo. Only through the creation and distribution of unpleasant feminine perspectives, like Flynn’s novels, can we really see and understand the psychological impact of the societal chains that bound women to rage. Only then can we hold those responsible accountable, and maybe even enact some change. But of course, that is another uncomfortable prospect.