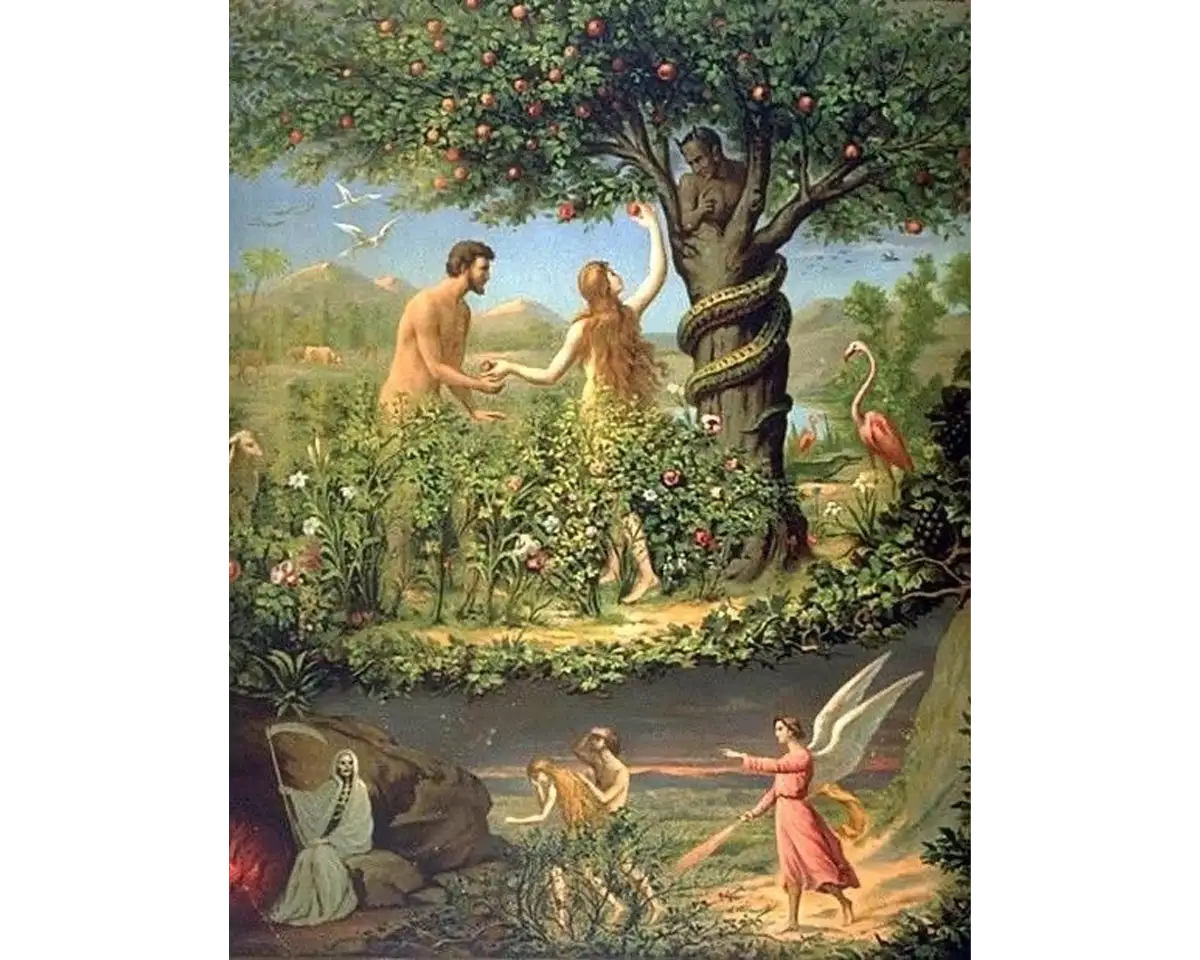

Throughout history, female desire has been overlooked, hidden, and stigmatized. If stories are a means of reinforcing social codes and acceptable behavior, women in literature were either delicate creatures, portrayed as models of purity and innocence, or dark, manipulative, and sinful cautionary tales. You could be the Virgin Mary or, on the contrary, the selfish and foolish Eve. And who would like to be the latter? After all, she was the one who couldn’t resist the temptation from the Devil, in the form of a snake, and bit the forbidden apple, convincing Adam to do the same. Because of her, we were kicked out of Paradise by God.

This binary has proven to be a twisted means of suppressing women’s desires. The narrative surrounding women’s virtue or sin has always been clear and has heavily permeated culture, inevitably resonating in classical literature and the following stories. Jane Eyre (1847) was courageous enough to explore female desire by advocating for personal acceptance and exploration. Anna Karenina (1877) illustrates the fatal consequences of sin within a social critique. Mina’s character in Dracula suffers from her desires, yet she is rewarded for not succumbing to them.

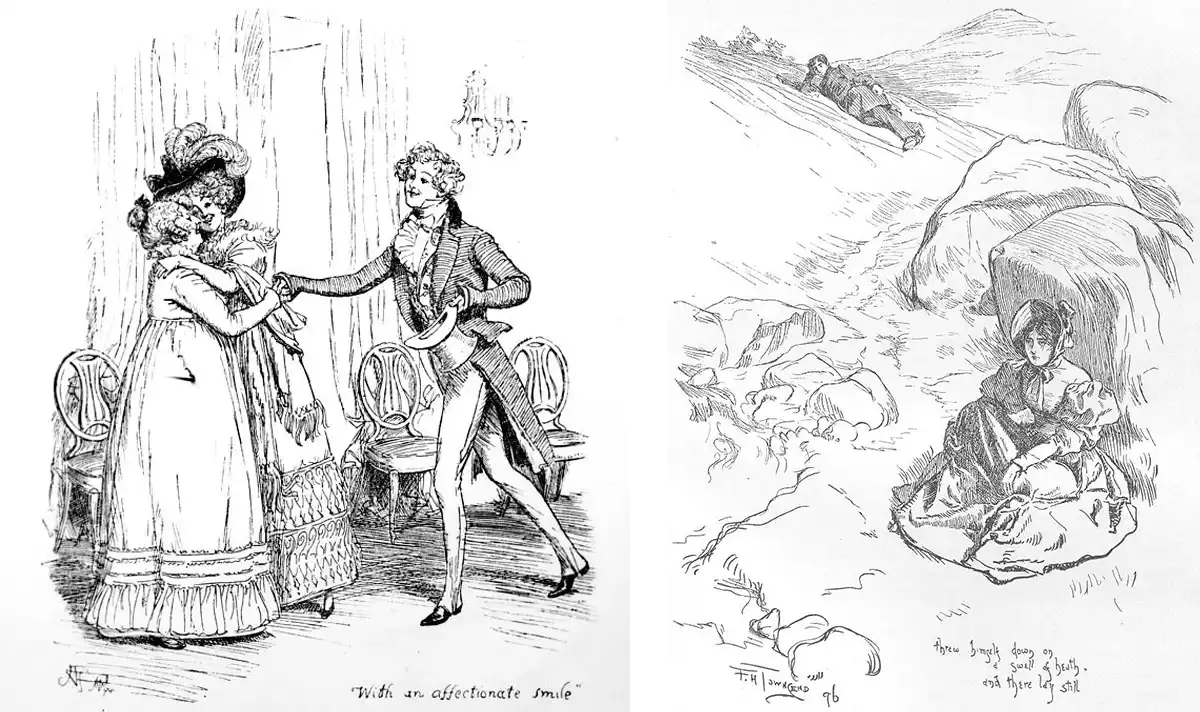

It is not hard to understand why Jane Eyre’s message scandalized 19th-century English society. While many were captivated by Charlotte Brontë’s strong and independent female protagonist, others were shocked by the complexities of female desire and love outside societal expectations. Pride and Prejudice had been published merely 30 years before; a romantic, fun, and socially correct story about a woman who pursued love instead of simply fixed matrimony. Fair enough if you ask me. While I wouldn’t dare to disrespect Austen’s story, Jane Eyre, on the other hand, is raw, dark, dramatic, and goes against 19th-century standards of propriety. I remember being scandalized by the intensity emanating from the pages of Brontë’s work.

Brontë portrays Jane as a deeply passionate character and encourages her to live all that’s possible to a woman of her period, to take as much as she can. That is the only real reason behind Jane’s rejection of St. John’s proposal. When he tells Jane about his plans for both of them in India, she doesn’t hesitate a moment to take this opportunity. But not as his wife, as she knows that his vision of marriage is of duty and submission. Only then does she return to Rochester because she comprehends that Thornfield is where she truly belongs. It is where she first built a life of her own; the place she felt truly at home. It is where she managed to be economically independent and where she experienced true, unconditional love. She knows it is far from perfect because of the age gap between her and Rochester. She knows it is far from correct or socially acceptable, as he is still married, yet she chooses it anyway.

Pictured right: illustration from Jane Eyre

Charlotte Brontë was not interested in reinforcing the established rules for women. The Scottish writer didn’t treat her protagonist’s desires, independence, passion, and wisdom as features to be tamed or repressed. Jane Eyre’s disruptive approach to women’s roles was based on the acceptance of women’s desires, even when they were socially unacceptable. In the end, Jane doesn’t perish because of her sins, but is instead rewarded with what we understand by a happy ending.

On the contrary, Anna Karenina is one of those classic Russian literature tragedies that I cannot help but return to again and again. Who among us didn’t desire that Anna’s and Vronsky’s destiny would be different? If not for the couple to be together, at least for Anna to have a better ending. From a modern perspective, the punishment she suffers for her desires and sins is raw and cruel.

Leo Tolstoy states throughout the novel that sin has a price. But for whom? We are introduced to this Russian aristocratic world through the story of Anna’s brother, Stiva, who has been unfaithful to his wife several times. Not only does he not regret his affairs, but he excuses his infidelity by alluding to the belief that boundless sexual desire is intrinsic to men’s nature. Not only does he indulge in this supposedly inherent behaviour, but he enjoys his nature without any reprimand from society.

Anna, on the other hand, is punished for similar acts. As her mental health becomes more severely compromised, we realise that her forbidden desire is not actually for Vronsky, or at least not anymore. What drives her mad is the certainty that, as a woman, she cannot keep all her privileges because she has indulged in sin. She realizes that society won’t ever forgive her, nor turn a blind eye to her sins, like they did to Stiva, a man. What she truly desires is to be treated like a man, to be allowed to keep all her privileges despite having indulged in sin.

Tolstoy’s intention with this story was to critique the hypocrisy of 19th-century Russian society. But of course, his deep religious beliefs shaped Anna’s tragic fate. Anna Karenina reinforces the narrative about the fallen woman who deserves punishment for her sins. She loses everything she had: her status, her children, and even her life for doing exactly the same as a man would do. Anna was brave to challenge the unwritten rules of society, but she couldn’t cope with the rejection that would come with it.

What is more forbidden than evil itself? ’s horrid and tragic yet romantic story has endured in popular culture to this day. It may be the most complex example of the three because of its symbolic and twisted representation of the unconscious attraction to the prohibited, a theme that Gothic literature has long explored.

The Victorian society the novel describes was one heavily marked by strict sexual morality. Dracula is obsessed with Mina because she is the replica of his dead love and embodies the purity of the ideal Victorian woman. Mina, on the other hand, is seduced by the dark, foreign, and unknown elements of life that Dracula embodies. Despite Mina’s virtue, she still succumbs to the power and knowledge that the Vampyre has to offer, almost paying with her humanity. Desire here is not equal to romance, but a symbolic way of craving freedom from societal restrictions.

The way desire functions in this novel is deeply twisted. Mina and Dracula’s psychic connection through his blood has often been read as a metaphor for repressed sexual desire as well as the fear of losing control of oneself. She frees that part of her repressed psyche, and abandons herself to the evil and primal instincts that we all have, but are usually too afraid to set free. Despite this, Stoker was more benevolent to his female heroine than Tolstoy, allowing her to touch the darkness without a fatal destiny. Mina’s figure is redeemed at the end of the story, after Dracula is destroyed, and she returns to her husband and her mortal life.

What is hidden underneath all these stories is not the forbidden romantic love for another person, as many may think. It is women’s forbidden desire to be free from the chains that their respective societies have imposed on them. The key to the disruptive success of the mentioned novels lies in portraying heroines who, despite their destiny, went against the rules of a society that would encourage women to keep on the path that has been dictated to them. They rejected Mary and chose Eve instead.