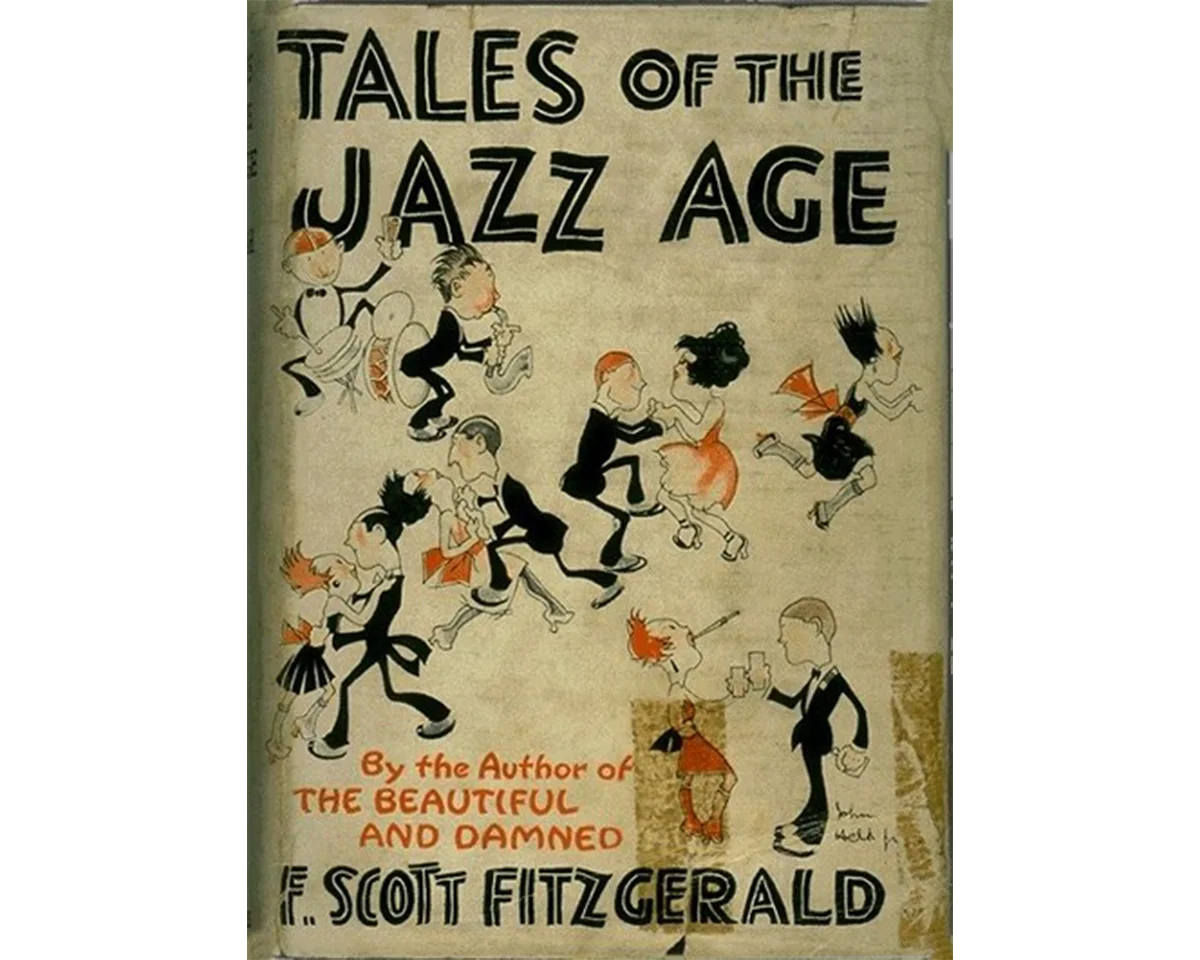

If it was the glittering visuals of Jay Gatsby’s parties that made them legendary, it was the music that pulled West Egg’s finest off their lawns and through his front door. F. Scott Fitzgerald knew that there was something special—something different—about the 1920s as early as 1922 when he popularized the term “the Jazz Age” in his short story collection Tales of the Jazz Age, and would, that same year, decide to use jazz as the auditory backdrop for his magnum opus, The Great Gatsby. The upbeat rhythms of jazz pulse and flow through Gatsby’s riproaring fêtes becoming a transportive vehicle through which partygoers embrace their wildest selves, moving and grooving to its infectious rhythms and dynamic beats.

Indeed, when Fitzgerald set out to write The Great Gatsby in 1922, he saw a society on the cusp of change, one that just so happened to be embracing more fluid forms of gender expression, fashion trends, and social norms at the very same time that jazz was spreading beyond its African American origins into broader, whiter audiences. Fitzgerald portrays jazz in Gatsby as an intoxicant, opening Chapter 3 with, “There was music from my neighbor’s house through the summer nights. In his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars.”

Like drinking five glasses of champagne, jazz music casts a spell on Gatsby’s guests; when the orchestra begins playing “yellow cocktail music,” suddenly, “laughter is easier, minute by minute, spilled with prodigality, tipped out at a cheerful word.” On the surface, it’s a scene of carefree revelry, filled with ease and joy. But as anyone who has spent time in Gatsby’s literary orbit knows, there’s a darker subtext to music in the novel, one that may just prompt you to rethink that line about laughter spilling from Gatsby’s guests as easily as their alcoholic beverages.

Now those who deeply know Gatsby (or who have had the pleasure of reading my brilliant colleague Nesha Ruther’s take on the novel’s urgency) may already be familiar with the unconventional reading of Jay Gatsby as a racialized other. Sparking many reimaginings of the novel, this reading centers Gatsby as a culturally hybrid figure who attempts to transcend the boundaries of social class—by becoming a self-made man—but tragically fails. That’s not to say that James Gatz is Black, but rather that he symbolizes Blackness, or the cultural intermingling of race, class, and social boundaries that have long come to define America.

With this context in mind, it becomes easier to see how Gatsby’s parties are a physical setting and metaphorical space where elites can let down their guard, exploring and embracing new possibilities—and maybe even entertaining the idea of cultural mixing. And yet, far from describing these lavish affairs as free from racism, Fitzgerald clearly distinguishes the jazz that plays at Gatsby’s parties from that of the Black-run jazz clubs of Harlem. Removed from the kind of loose-limbed, blues-drenched music with deep roots in African American traditions, the large, formal orchestra playing at Gatsby’s mansion in Chapter 3 offers a zipped-up version of authentic jazz adapted for white audiences.

In the wake of World War I, white Americans developed a renewed fascination with Black culture, though often through the lens of exoticization and control. Jazz in particular became a site of both desire and anxiety, something that can be pinpointed in Fitzgerald’s descriptions of jazz, when examined closely. When the orchestra at Gatsby’s first begins playing, for example, “The lights grow brighter as the earth lurches away from the sun,” a dramatic description that, when taken literally, suggests that the earth is being covered in darkness.

The genre’s associations with sensuality, improvisation, and rebellion made it thrilling to white audiences, even as they sought to distance themselves from its origins. Through the otherworldly, quasi-apocalyptic setting that its music provides, revelers become “excited with triumph,” Fitzgerald writes, as they “glide on through the sea-change of faces and voices and color under the constantly changing light.”

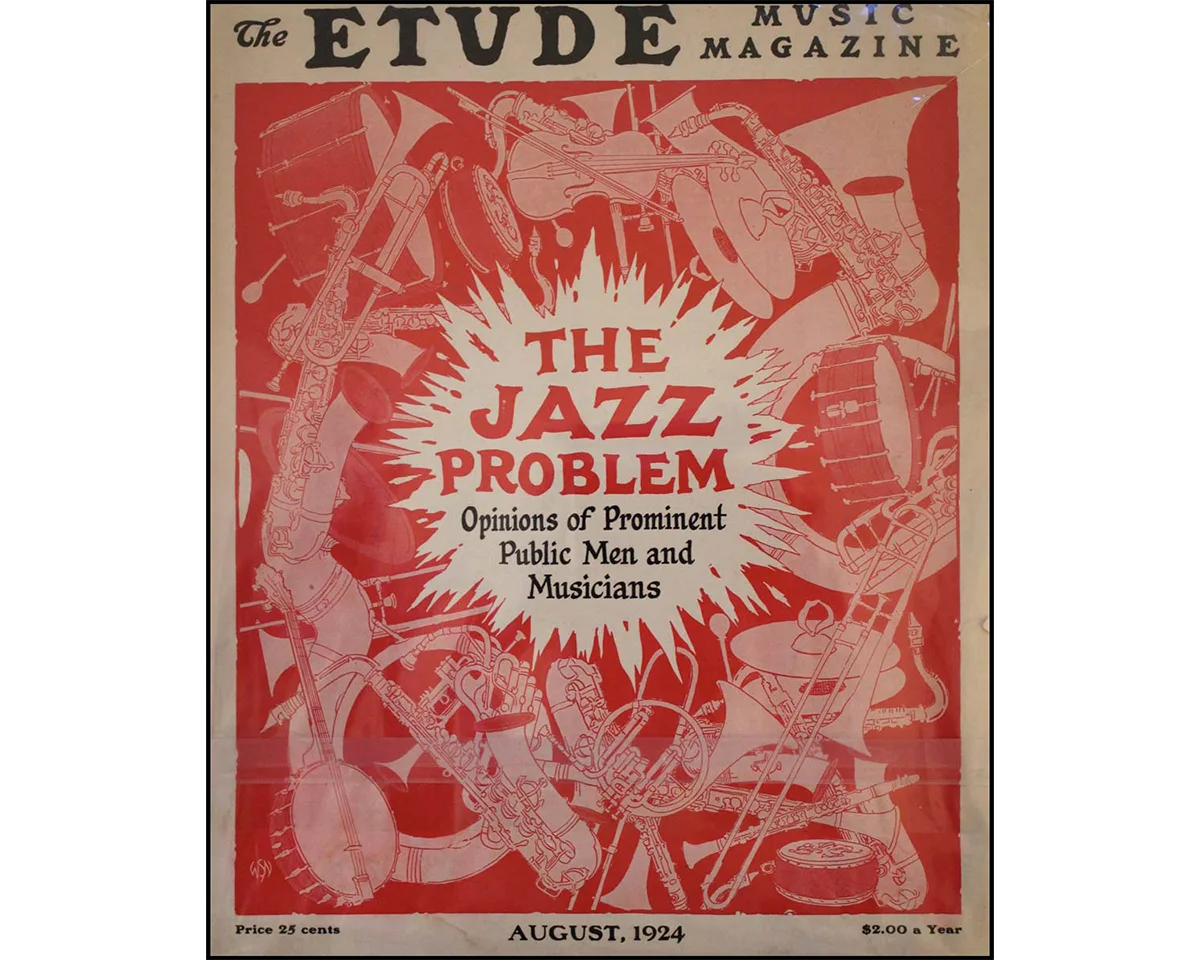

Outside of the novel, loosening cultural mores ushered in by the freedom of jazz and all that it represented sparked a moral panic among whites that came to be known as “The Jazz Problem.” A 1924 issue of The Etude magazine—a popular music teacher’s magazine during the first half of the twentieth century—dedicated entirely to jazz gathered perspectives from prominent critics and musicians in the industry, and while their opinions varied, the magazine’s editorial team wrote, “In its original form it has no place in musical education and deserves none. It will have to be transmogrified many times” before it can be seriously considered. In case that wasn’t clear enough, the bitter dismissal continues, “We, therefore, do most emphatically not endorse Jazz, merely by discussing it.”

Despite coining the term the “Jazz Age,” Fitzgerald’s description of the large band at Gatsby’s party reveals more than an initial read may let on. Nick describes the “cocktail music” as “yellow,” a word that can carry racial connotations, and subtly evokes jazz’s association with “devil’s music” by referring to its “pitful” of instruments. When he describes the band as “no thin five-piece affair,” he emphasizes not just the orchestra’s size but also its expanded repertoire, perhaps implying that the band is better suited to cater to the white elite. White musicians like Paul Whiteman had large ensembles and expanded repertoires and while he may have been called by Duke Ellington “the King of Jazz,” his fame is complicated by the fact that Black bandleaders had expanded ensembles at least 10 years before he did. Like so many other white musicians, Whiteman became famous for appropriating Black jazz traditions and “sanitizing” them for white audiences—a 1924 concert of his went down in history as the night he “made a lady out of Jazz.”

Ultimately, Fitzgerald both reflects and critiques white society’s ambivalence toward jazz. On one hand, he uses jazz as a seductive backdrop for Gatsby’s partiers, enticing partygoers to live freely, and loosely, while on the other, he subtly indicts the very elites who would have denounced more authentic forms of jazz by critiquing their moral disregard. Yet perhaps most telling is the fact that Black Americans appear rarely in the novel and always on the periphery. Although Tom’s apartment on 158th Street is just north of Harlem, the cultural capital of jazz in the 20s is never mentioned, not even in passing. Jazz in The Great Gatsby functions like race—as a societal issue whites can tune in when they feel like it, and just as easily tune out.

Recommended Further Reading