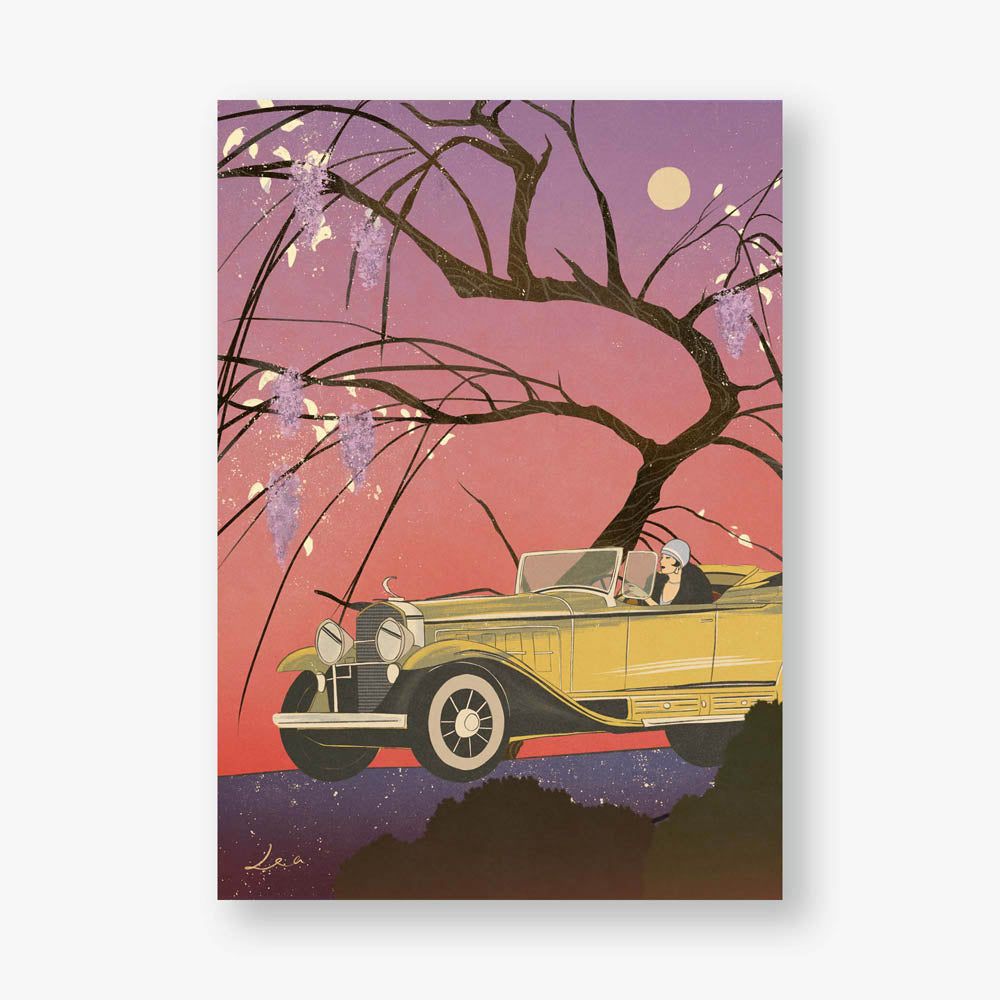

When you’re a teenager, it can feel like a chemical reaction occurs whenever a teacher tells you to read a book. Classics become convoluted, brilliance becomes bleak; the supposed relevance of the book seems cringey and insincere. For many, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby somehow defied that transformation. It was fresh and vivid, with its acid green lawns, glittering beaches, and shiny yellow cars, it seemed to leap from the pages and propel you into a world so far outside the scope of your tenth-grade English class. Of all the books the American public school system demands we read, Gatsby likely comes out as the most beloved. And yet I think it is a mistake that we are made to read the book so young, because many of us go on to never read it again. And that, Old Sports, is a tragedy beyond compare.

At the start of an intensive period of research I do for all Bond & Grace Art Novels, I revisited The Great Gatsby for the first time since high school. I was prepared to like it. I wasn’t prepared for it to be one of the most important and timely books I had read in years. Once, it transported me to a world very far from my own. Now, it revealed that I had actually been living in that world all along.

Here are four of Gatsby’s essential themes that I didn’t understand back then, that make this book the most urgent read of the 2020s.

1. “Voice Full of Money” - Gatsby As a Recession Indicator

F. Scott Fitzgerald has won over generations of high schoolers with his depictions of the rowdy, wondrous environments of 1920s speakeasies, parties, and abundant wealth. And yet he also captured the looming threat of economic recession that would devastate the country in the 1930s. As high schoolers wander champagne-drunk through the lavish rooms of Gatsby’s mansion, they likely miss the novel’s true message: that luxury, aspiration, and enchantment comes at the cost of moral rot, industrial waste, and widespread economic suffering. While many of us may remember Gatsby as a quintessentially American success story, the novel instead suggests that the gates of high society are carefully guarded, propped open only to those born into wealth and privilege.

It is in this context that Gatsby finds himself in West Egg, a fictional place based on Great Neck, Long Island, where Fitzgerald spent much of 1923. It was in Great Neck that Fitzgerald encountered Jazz Age excess at its most extreme, witnessing the wealth and extravagance of both the old money and the nouveau riche in their opulent estates along the Gold Coast. With no shortage of inspiration for a novel about celebrity, scandal, and the lives of the wealthy, Fitzgerald wrote to a friend in 1922, remarking that “Great Neck is a great place for celebrities,” one that is “most amusing after the dull healthy middle west.”

It has been well-documented that in times of economic hardship, we crave content that allows us to look into the lives of the wealthy and elite. Networks pour millions of dollars into reality tv so that we can live vicariously through the luxurious lives of the few. Many feel strong emotional ties with celebrities and the uber-wealthy while struggling to pay their bills. In this way, Gatsby is nothing if not a recession indicator.

2. “Careless People” - How the Wealthy Manipulate and Discard the Poor

Fitzgerald too noticed the startling juxtaposition of the classes. The contrast of Long Island’s North Shore, a playground for the well-heeled, with the abject poverty, hopelessness, and suffering that arose alongside increased industrial output and manufacturing alarmed and disturbed him. The barren, industrial wasteland filled with dust and smog was likely inspired by the real-life Corona Ash Pits in Queens—a dumping ground along the Flushing River where coal ash from New York City was transported by rail. Through imagery drawn from T.S. Eliot’s 1922 poem “The Waste Land,” Fitzgerald brought the region to life, capturing how the material desires of the elites both literally and figuratively kill the poor, turning them into “ash-grey men, who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air.” It is in this context that we encounter the Valley of Ashes and its residents, Myrtle and George Wilson—figures recognizable to anyone who has spent time in today’s blue-collar American communities.

Indeed, Myrtle and George strike a chord for anyone accustomed to poverty; whether rural or urban, white or Black, there is something painfully familiar about the Wilsons’ desperation. Both members of the couple latch on to the wealthy Tom Buchanan: Myrtle by having an affair with him, George through the misguided hope that Tom will sell him his car. In the end, the couple are used and discarded by the novel’s wealthier characters, buried in silence and shame.

From horrified Trump voters who have learned that their candidate is cutting the very social services that sustain their lives, to the shocking controversy over Luigi Mangione’s murder of United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson; the way the wealthy manipulate, use, and eventually discard members of the working class finds a direct parallel in The Great Gatsby.

3. “Mr. Nobody From Nowhere” - Gatsby as a Racial Other

Amidst this world of vast social stratification, America was also undergoing a demographic transformation in the 1920s. The country saw a major influx of immigrants, particularly from Eastern and Southern Europe, as well as the Great Migration, where roughly 500,000 African Americans migrated North to flee the Jim Crow South. These shifting demographics stoked anxieties about the loss of white hegemony, as seen in Tom Buchanan’s racist tirades. In the late 1910s, the Ku Klux Klan’s membership swelled to the millions and enjoyed the respectability of a mainstream civic organization.

Part of what makes Gatsby such an enigmatic and widely interpreted figure is that Fitzgerald notably associates him with New York’s changing demographic landscape. Despite Gatsby’s whiteness and new wealth, he is a metaphorical symbol for all those who lack either. Just as race in America is about drawing unfounded assumptions between skin color, behavior, and social capital, Fitzgerald’s elite characters draw nebulous conclusions about Gatsby, seeing his rise to sudden wealth as reprehensible. By linking Gatsby with Blackness specifically and cultural otherness more generally, he becomes representative of those in America who have been denied visibility—a figure in which all Americans can see some part of themselves.

Tom articulates the threat that Gatsby represents to the racial order most clearly, stating, “I suppose the latest thing is to sit back and let Mr. Nobody from Nowhere make love to your wife… Nowadays people begin by sneering at family life and family institutions, and next they’ll throw everything overboard and have intermarriage between black and white.” In this scathing rebuttal, Tom implicitly links Gatsby’s courtship of Daisy with racial mixing. In Tom’s worldview, Gatsby has drastically overstepped socioeconomic borders, and acceptance of someone like Gatsby gives way to acceptance of dreamers of all backgrounds and demographics.

Today, the anxieties about cultural diversity are just as acute as they were in the 1920s. From increased aggression from Immigrations and Customs Enforcement against both undocumented immigrants and legal green card holders, to bans on teaching matters of race, politics, sexual orientation and gender identity in schools, the question of who is considered American is just as fraught now as it was in Fitzgerald’s time. It remains impressive that in an era in which it was all too easy to disregard the experiences of those who were not white, Fitzgerald identified this theme and created a protagonist who reflected it.

4. “Can’t Repeat the Past? Why of Course You Can!” - Gatsby as Self-Mythology

For the adolescent reader, Jay Gatsby seems the perfect embodiment of the self-made man. He is born to poor farmers in North Dakota, but rejects the identity of James Gatz and forges a new one: Jay Gatsby. Gatsby is cool, mysterious, astonishingly wealthy. He throws spectacular parties and drives a yellow convertible and wins back the girl of his dreams. If it seems like Gatsby is a teenage fantasy come to life, that’s because he is. Fitzgerald tells us as much in Chapter 6 when describing Gatsby’s origin story. He says, “So he invented just the sort of Jay Gatsby that a seventeen-year-old boy would be likely to invent, and to this conception he was faithful to the end.”

But to the adult reader, a portrait of a man so committed to a version of himself created when he was a teenager is at best, cringey, and at worst, pathetic. Gatsby is in some ways emotionally stunted, too bound to a single dream—and the woman he centers that dream around—to realize that the world has changed, moved on, and if he wants to survive, he must too. But Gatsby refuses, insisting he can defy the laws that structure the world around him.

When Nick tells him to go easy on Daisy, and that “You can’t repeat the past,” Gatsby, shocked, declares, “Can’t repeat the past? Why of course you can!” Gatsby does not simply want Daisy back in his life, he wants to erase any time she wasn’t. He demands she tell Tom that she never loved him, and when she crumbles, insisting she loved them both, Gatsby, awestruck, says, “You loved me too?” It is inconceivable to him that a world in which Tom and Daisy have their own private relationship could exist. It is inconceivable to him that perhaps it is simply too late.

In a world in which we share the best, polished version of ourselves online. Or perhaps more concernedly, record our most vulnerable and intimate moments for public consumption, we constantly curate and perform our own self-mythology. It becomes harder and harder to think of ourselves as real, complex people, and more like a brand, an aesthetic, a piece of content.

The Great Gatsby reminds us of the dangers of sacrificing our lives in service of a dream, and the cost of dehumanizing both ourselves, and those around us. Perhaps if Gatsby had a truer understanding of who he really is, he could have expected less from Daisy, and the pair could end up happy after all.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby isn’t just a classic, it's a cautionary tale, a timely warning against the dangers of our modern world, and a reminder that perhaps these problems aren’t as new as we think they are. From shows like Succession to films like Anora, we remain a country and culture that is obsessed with wealth, status, and privilege, while also being aware that those very things conceal an insidious undercurrent. 100 years later, we’re still telling the same American story as The Great Gatsby—new heroes, new villains, same disappointment and disillusionment.

If you’re going to do one thing this year, re-read The Great Gatsby. You might think you know it from high school English, but there’s so much more to this book than meets the eye (or eyes—staring out at you hauntingly from a billboard).