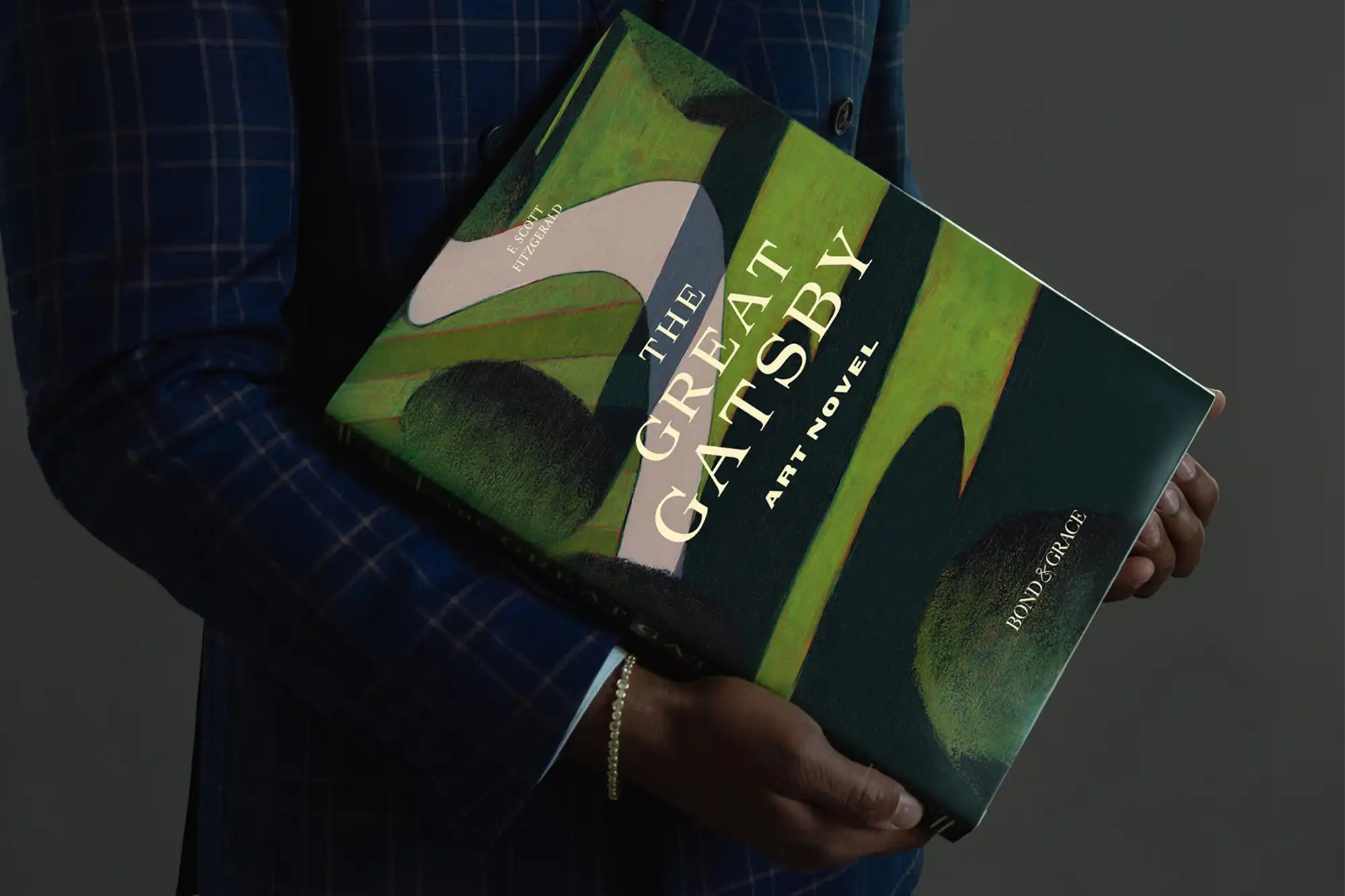

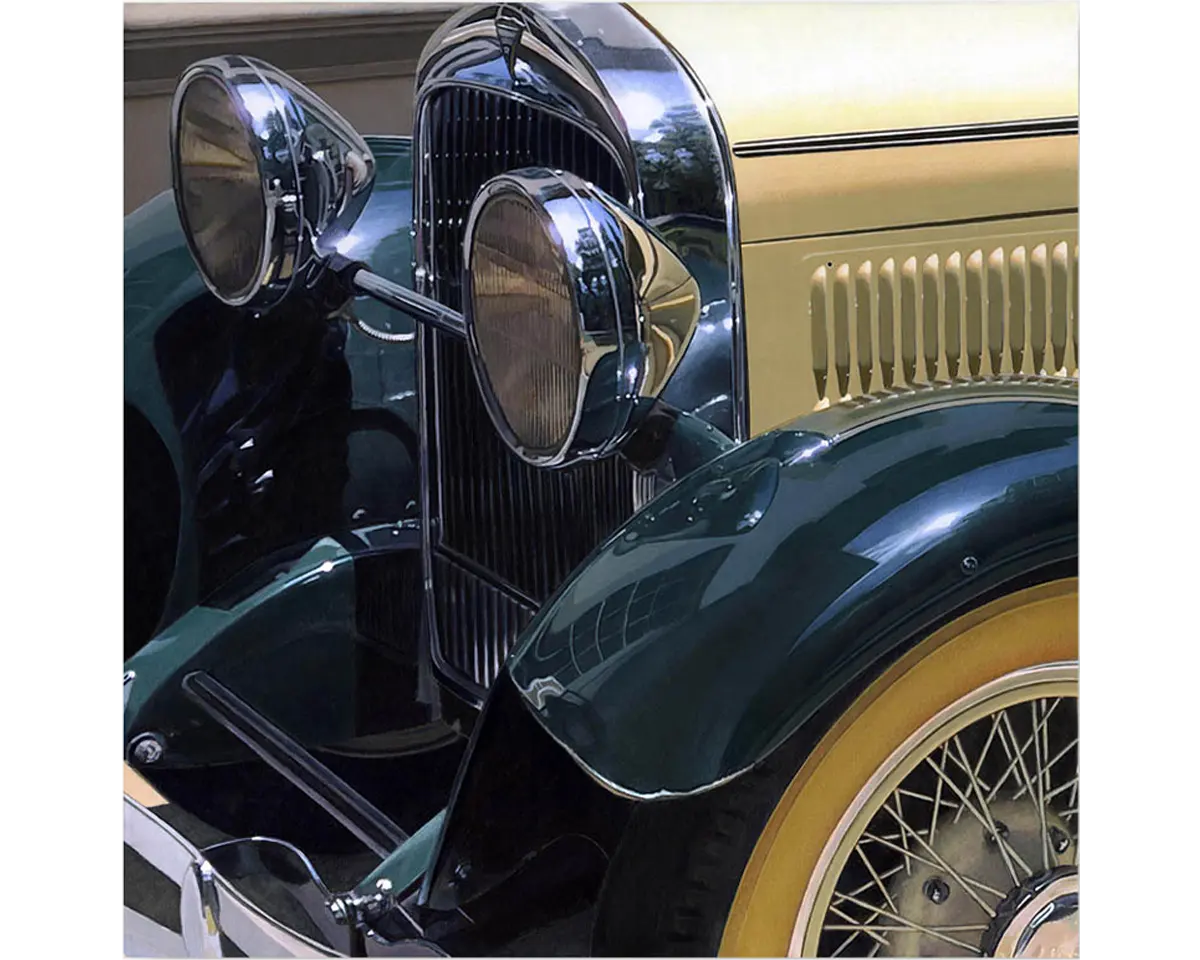

Each year, in the final stages of Art Novel development, our Creative team thoughtfully selects one singular artwork from the Art Novel’s accompanying art collection to grace the dust jacket of the “Art Cover” edition. Choosing from a centennial collection of 55 incredible new artworks created this year in direct response to The Great Gatsby is no easy feat—the work must encapsulate the creative, editorial, and curatorial spirit of the entire Art Novel. It must reflect class and wealth disparities, the elusive essence of Gatsby’s dream, and that distinctly American drive for better lives and flashier cars.

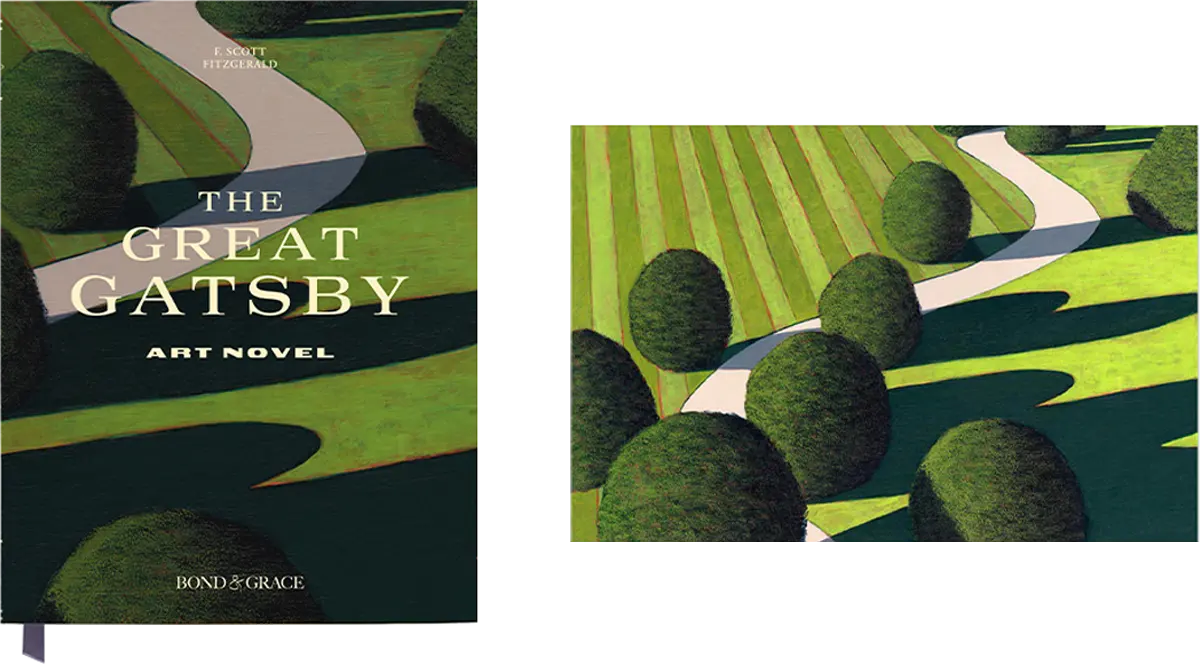

One work, however, stood out to Maggie Lemak and Romina Krosnyak, our award-winning designers: Leah Giberson’s A Shadowed Path (2025), a painting that brings vivid realism to Fitzgerald’s landscape, setting the vast Midwestern plains of the author’s origins across the road from the manicured lawns of West Egg. Straying slightly from her typical process of layering both paint and pigment prints on her substrate, Leah uses acrylics alone to beautifully juxtapose the stark geographic and class divides that underpin not only The Great Gatsby but the American social landscape at large.

In A Shadowed Path, Leah captures the tension between humble beginnings and glittering facades, between authenticity and performative achievement. “The contrast between the cultivated farmland on top and the manicured lawn on the bottom was important to me as a way of pointing to the meeting of and division between two different worlds,” Leah muses. Indeed, Leah’s red underpainting peeks through the dramatic crop rows that recede beyond the Northwest edges of the panel, appearing slightly less polished than the immaculate tightness of Gatsby’s lawn on the East side of the winding road.

For Leah Giberson, a painter based in Massachusetts, rereading Gatsby and uncovering the metaphors, truths, and subtext cloaked beneath Fitzgerald’s lyrical prose mirrored the process of seeing and re-seeing that is core to her creative practice. Working from her own photographs, Leah typically crops and reassembles images onto panels as pigment prints, then paints over them, deciding which details to keep, heighten, or erase. “My work lives somewhere between photography, collage, and painting,” she says about her process. “I almost feel like an archaeologist as I’m unearthing these second stories, these hidden relationships and moments that are easily missed if you don’t look closely.”

Drawing on the concept of a memory that warps or embellishes with time, Leah’s practice is all about analyzing perspectives and deciding which elements of the story are hers to tell. “Sometimes we take seemingly disjointed experiences and put them together, or we might oversimplify some areas and add extra details to others, in an attempt to find meaning in our experiences,” she muses. Leah positions herself as a kind of arbiter of truth, empowering herself to reshape the story.

As she homed in on her concept for A Shadowed Path, Leah thought intentionally about what Gatsby’s longing for Daisy, and for acceptance among Long Island’s elite, says about the American Dream 100 years later. When you peel back the layers of the American facade, you find a disenfranchised lower class, stark class disparities, and the marginalization of communities from a wide array of racial and economic backgrounds. And yet, we all still reach—whether it be for the next job, the bigger house, or simply the paycheck that keeps food on the table. Leah views the hedges in A Shadowed Path as characters from the novel, each trailed by the ominous shadows of their own longing. She hopes viewers will be moved to look closer—at her paintings, and at the overlooked details in their own surroundings. Greatness, to her, “isn’t in perfection, but in the capacity to shift perception and unearth the quiet narratives that live along the edges of attention…. in the fractured in between spaces where both uncertainty and possibility exist.”

Often using the interplay of light and darkness to reveal an unsettling stillness, the five works in Leah’s Gatsby collection illuminate the haunting underbelly of American perfection. A lone lounge chair and abandoned martini glass baking in the morning light; a ladder vanishing beneath the glow of a poison-green pool; headlights glowing like all-seeing eyes; a damp towel asking, is anyone there? Paradoxes abound: a party-scene but no revelers, a pool too eerie to enter; grand hedges casting outsized shadows. The hyperrealistic precision with which these scenes are depicted only deepens their mystery. Just as her paintings prompt us to probe the happenings within each scene, they also pose a more fundamental question: are these photographs, or could they be flawlessly rendered paintings? Existing somewhere in between the two mediums—and executed with the exacting skill of a person fastidiously attuned to detail—Leah’s work demands that we enter into a process of questioning and seeking.

Fittingly, this concept of finding truth runs throughout the novel and throughout our curatorial approach to the wider collection. In the novel, Gatsby is seen as blasphemous for concealing his origins and reinventing himself, yet deception saturates the world around him; no character “out East” lives a life remotely authentic to their heart’s desires. Even the tale itself unfolds two years in retrospect, shaped by the perspective of a narrator who was admittedly enraptured by Gatsby’s magnetic charm—his irresistible smile that “concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor.” Fitzgerald invites us to peel back the layers of illusion, to undress the meaning beneath the glitter, to step past the pruned hedges of Gatsby’s lawn and onto the open plains of truth. Though our vision will always be shaped by bias, both Fitzgerald and Leah challenge us to look closer anyway—to catch, if only for a moment, a vivid glimpse of truth.