Historically, the topic of voyeurism has had negative connotations, particularly as it relates to the “Peeping Tom” figure—a term that traces back to the seventeenth century and is linked to the medieval legend of Lady Godiva. Voyeurism has long been explored through the medium of literature and film, yet most often from a male lens, as seen in iconic examples such as Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. In such stories—and the male-centric term “Peeping Tom” illustrates—men typically play the role of the active observer while women are passively witnessed. And while women, particularly middle-aged women, have often been overlooked in the arts, an explosion of female-led stories starring older women has dominated literature and film in recent years.

After generations of being objectified in storytelling, women—and often, older ones—are now being granted a stage to explore themselves, their sexuality, and their bodies, through works that tackle themes of ageing, desire, intimacy, and the female experience. Even voyeurism is now being examined through the female gaze, giving older women the agency, voice, and sexual impulses that they have long been denied.

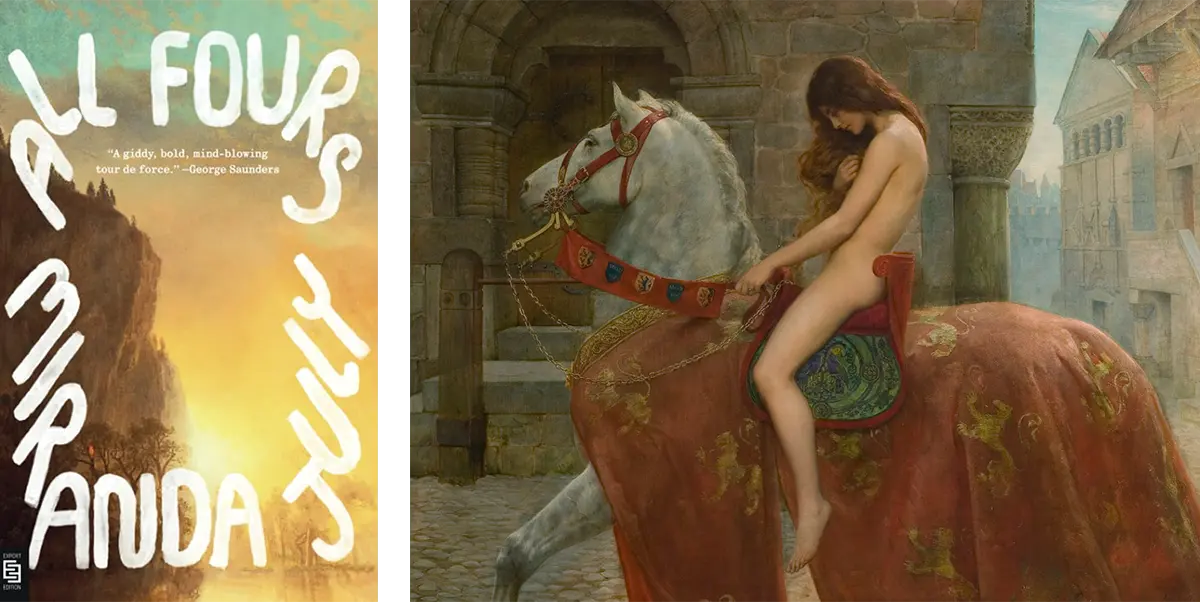

Recognized by the New York Times as the “first great perimenopausal novel,” AllFours (2024) by Miranda July offers a prime example of a novel that flips the script on voyeurism. The story features a successful artist who celebrates turning 45 by gifting herself a cross-country trip away from her husband and child before spontaneously stopping at a nearby motel for two weeks and having an affair with a local man named Davey. Offering a key entry point into the novel, this unnamed narrator enjoys being watched; the book opens with a neighbor sending her a note telling her that someone has been taking pictures through her windows from the street. While initially she is worried, we soon see July reversing the traditional scenario where the male gaze is used for his own sexual gratification: the narrator ends up fantasising about her photographer’s arousal and gains agency over her body.

Excited by the experience, the protagonist describes herself as “a kaleidoscope, each glittering piece of glass changing as I turned.” She reveals, “For me, lying created just the right amount of problems and what you saw was just one of my four or five faces—each real, each with different needs.” Her comment highlights the challenges women face in their daily lives—balancing the competing responsibilities of work, marriage, motherhood, and desire.

Similar themes run through Halina Reijn’s film Babygirl (2024), which sees Nicole Kidman’s CEO character Romy risk her career and family when she embarks on an affair with young intern Samuel. Like AllFours, the story highlights the shame and stigma that women are subjected to surrounding sexuality. Neither Romy nor the unnamed narrator in All Fours are able to express their desires honestly to their husbands. Like a child covering their eyes in hopes of becoming invisible, Romy hides under a sheet in bed when she confesses to her husband Jacob what she really wants sexually.

In a scene at a work party, Romy’s power as CEO is absent when she is dancing with her family in the presence of Samuel, who is with another woman. The use of Robyn’s “Dancing on my Own” perfectly captures the subtext of the scene—“I’m in the corner watching you kiss her, oh/I’m right over here, why can’t you see me?” July uses the same device in All Fours when the narrator dances alone at a party and her husband Harris watches from across the room. Their intimacy is seen with their secret salute—“At this slight remove all our formality falls away, revealing a mutual and steadfast devotion so tender I could have cried right there on the dance floor.” Yet prior to this moment, the narrator senses that Harris disapproves of her dancing and sees it as provocative. In this sense, Harris’ voyeurism (watching his wife dance) has the ability to create both intimacy and shame when it comes to the narrator’s desires.

Dance offers the protagonists of All Fours and Babygirl a form of escape. In contrast to Harris watching his wife dance, Babygirl sees Reijn subvert the male gaze, with Samuel becoming the object of female desire. In the “Father Figure” dance sequence, Samuel is performing topless, while Romy indulges in being the voyeur. The lyrics of the song embody both characters’ feelings and how Romy wants to feel seen—“That’s all I wanted/Something special, something sacred/In your eyes.”—with Samuel taking on the role of the mentor.

Dance is used to show how both women come to discover their voice. Unlike Romy, watching Davey dance is not about desire for All Fours’ protagonist. Instead, it becomes a moment of clarity when she realizes watching him dance to express their connection is the happiest she has ever been. Similarly, Romy dances freely at a rave with Samuel, in a scene that pulsates with energy as the pair shed their inhibitions.

The use of dance as a form of voyeurism is further flipped on its head when All Fours’ protagonist posts a video of her own dance performance in the hope that Davey will see it and reconnect with her. Her decision to become the object of the male gaze is significant as she is voluntarily subjecting herself to it. Similarly, Romy indulges in role-play games with Samuel, even drinking a glass of milk from him in a bar while he observes from a distance. Yet in a contrasting scene, Romy is reluctant to obey Samuel’s order to take her clothes off. However, when he senses her vulnerability after she undresses, Samuel tells Romy with honesty that she is beautiful, which helps her find self-acceptance. The pair achieves a sense of true intimacy and now see each other for who they really are.

Davey and the narrator of All Fours also establish an incredible intimacy, even though they don’t have sex during their affair. Their immediate sexual connection is described through charged, suggestive language as early as their first encounter, when Davey cleans her car’s windshield:

“He was sliding the rubber edge across the glass with long, sure, steady strokes. It was hypnotic, like being bathed. I fell into a sort of lazy trance and for this reason I was slow to realise we had made eye contact. How embarrassing. But to look away would make it seem as if I cared what this person thought—he should look away. He didn’t, so we remained locked together like this as he made his way down the window.”

Unable to peel her eyes away, the protagonist’s voyeurism creates a sensual charge filled with erotic imagery and alliteration used to evoke sex. The simile of being bathed is used to represent the narrator’s rebirth as she embarks on her new journey. Interestingly, water imagery is also used in Babygirl to signify the change in Romy, with scenes of her and Samuel submerged in her pool.

Both women’s similar paths of self-discovery enable them to establish healthy and honest marriages going forward. The protagonist of All Fours uses role-play with Harris so they can speak freely to each other and discover what they really want from their marriage. Jacob and Romy manage to move on from her affair, and Jacob agrees to fulfill Romy’s desires, which appear to include her fantasising about Samuel when they are in bed.

Despite society’s lack of acceptance regarding women’s age, sexuality, and physicality, for these characters, voyeurism allows them to achieve liberation, exercise their agency, and use their voices. What Babygirl’s Romy and All Fours’ unnamed narrator have in common is that they are real women with flaws and feelings. The perception that a female character has to be likeable has become a common trope within Hollywood and publishing, creating unrealistic and unattainable expectations of women. Disillusionment with oppressive regimes against women has led to more female creators finding their voice, paving the way for better female representation and groundbreaking female depictions, with multifaceted characters finally becoming the new normal. Long may it last.