“Attention is the beginning of devotion.” —Mary Oliver, Upstream (2016)

When was the last time you let yourself be still enough to notice your life? Beyond the hum of constant social media updates and work to be done, never mind the news cycle’s violent tides; we are pulled in so many directions, pulled so far away from ourselves, that it can be difficult to notice what quiet things beg our attention. Our attention spans have always been one of our most precious resources and personal powers, but in a chaotic modern world, they often become short, inflamed, and burnt out. Writing, and more specifically poetry, is nothing if not the act of paying attention. Nurturing and healing our attention spans through mediums like poetry opens us up to the present moment, enabling our lives to become less burdened with the things we cannot control, and more enriched with the simple pleasures that surround us. Few poets have taught us more about this practice than Mary Oliver.

You, poetry fan or not, have likely heard of Mary Oliver, or seen a line from one of her poems on a coffee mug, t-shirt, or your friend’s Pinterest board. But one line only scratches the surface of the full depth a poem can offer. Giving ourselves time to read full poems, to explore a writer’s body of work, is a gift to our attention spans. Mary Oliver is one of our best-known and widely-read poets, and those who take the time to dive into her work come away with deep and lasting connections to it.

Mary Oliver was born in Cleveland, Ohio, and grew up in the nearby town of Maple Heights. She recalls in her essay “My Friend Walt Whitman” how in high school she would leave home in the morning and start walking to school, only to turn instead to the woods, always with a bag of books, Whitman always among them. Later in life, she would talk about the difficulty of her childhood home, and the abuse she experienced at the hands of her father, which informed much of her collection Dream Work (1986). In her interview with Krista Tippett for the On Being podcast, Oliver says: “It was a very bad childhood—for everybody, every member of the household, not just myself, I think—and I escaped it, barely, with years of trouble. But I did find the entire world, in looking for something. But I got saved by poetry, and I got saved by the beauty of the world.” The pairing of poetry and the natural world comes up over and over again in Oliver’s work, particularly her prose, where she explores the safety she found in both nature and literature.

As an adult, she attended both Ohio State University and Vassar College in the ‘50s but did not receive a degree at either institution. Instead, Oliver worked at Steepletop, the late Edna St. Vincent Millay’s estate, helping her sister, Norma, organize the poet’s papers. As a result, Oliver would challenge society’s expectations that in order to become an expert in something, you must complete a formal education. Her dedication to the craft of poetry is exemplified not only in her own work but in A Poetry Handbook (1994), a guide for writers she wrote during her time teaching at Bennington College. Oliver insisted that A Poetry Handbook be published only in paperback, as paperbacks are less expensive than hardcovers, and therefore more accessible to college students. Former Bennington students remember that despite Oliver’s many accolades, she treated their work like the work of a peer.

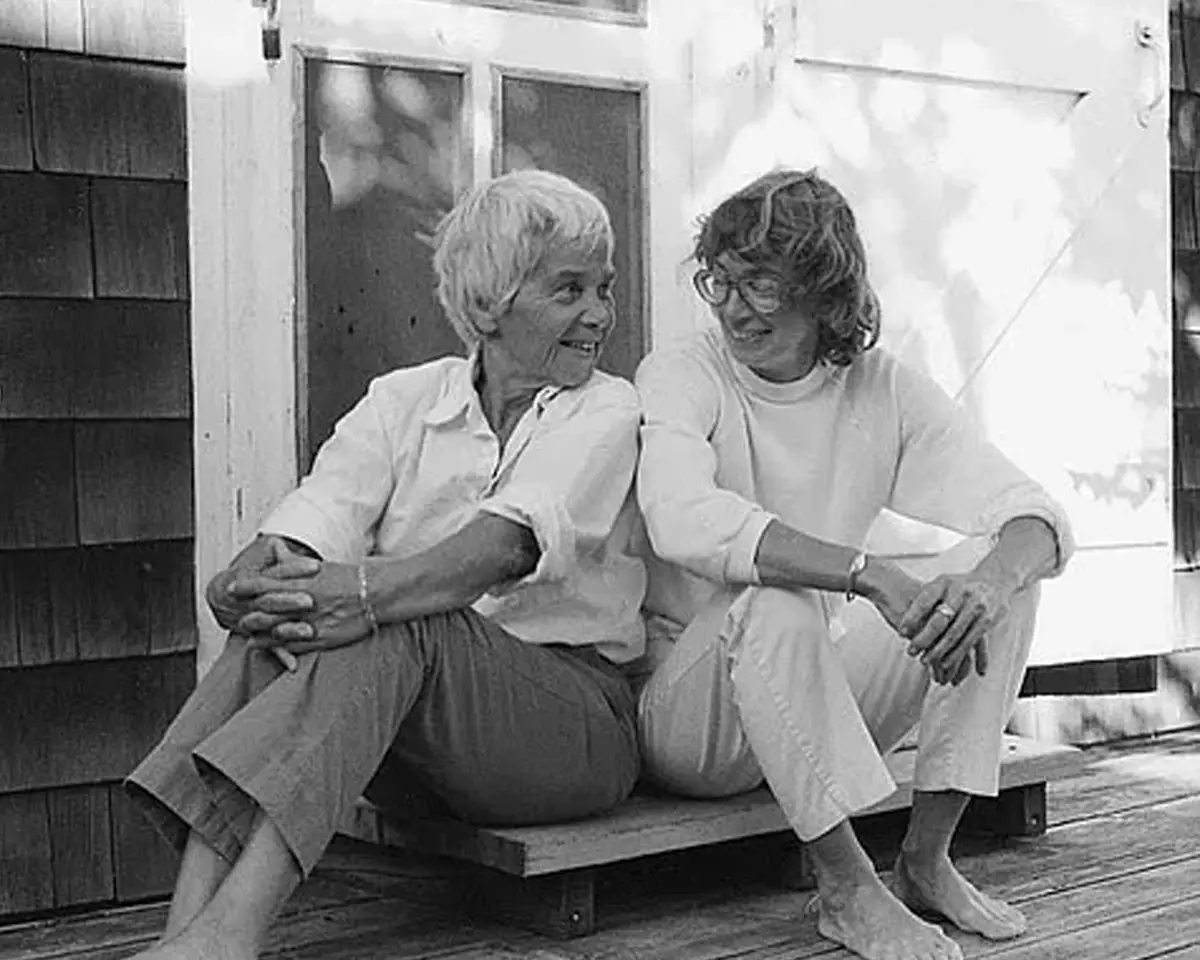

Oliver moved to Provincetown, Massachusetts, in the 1960s, where she and her partner, photographer Molly Malone Cook, spent four decades. In the audio collection Wild and Precious: A Celebration of Mary Oliver (2023), former students, friends, and even neighbors of Oliver’s offer rich anecdotes and stories about the poet’s life. Provincetown neighbors recalled how she would hide pencils in the trees around town to ensure she’d always have something to write with when she was out on her long walks. Much of her writing concerns the natural world of her rural Ohio upbringing and those years as an adult she spent near the shore. Her fourth poetry collection, American Primitive (1983), won the Pulitzer Prize in 1984, and New and Selected Poems (1992) received the National Book Award.

In 2012, Oliver underwent a long and arduous battle with lung cancer. One friend recollects that after Oliver received a clean bill of health, she still continued to chain smoke. Oliver herself remarked that though she got through the treatment, she felt as if “death has left his calling card.” She writes about this experience in her collection Blue Horses (2014), particularly in “The Fourth Sign of the Zodiac,” which is Cancer. In 2015, the poet received another cancer diagnosis, this time lymphoma. As Oliver underwent her final battle with lymphoma in 2019, her friends recalled reading Rumi to her at her bedside.

The portrait I have of Mary Oliver is one of a steadfast person going out into nature, notebook forever in hand, to notice the world and to tell about it. She became, what must be, a true student of life, of the world, and of paying attention. But I also recognize that she was human, and therefore imperfect. It is easy to have an image of someone so widely admired and forget that even with her clear lungs, she wanted to be able to have a cigarette.

It also serves as a reminder that none of us need to be living perfect or idealized lives in order to begin to pay attention to the beauty of the world. Oliver points this out in her much beloved poem “Wild Geese:”

“You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.”

We are all, in our varying states of joy and grief, always invited to look at what’s in front of us. The world is always available to us, and perhaps it is even more important for us to notice it when we are, personally and collectively, experiencing great hardship.

Throughout a prolific body of work, Mary Oliver invites us, again and again, to pay attention. She addresses the role attention plays in her work in her collection Our World (2009): “It has frequently been remarked, about my own writings, that I emphasize the notion of attention. This began simply enough: to see that the way the flicker flies is greatly different from the way the swallow plays in the golden air of summer. It was my pleasure to notice such things, it was a good first step. But later, watching M. when she was taking photographs, and watching her in the darkroom, and no less watching the intensity and openness with which she dealt with friends, and strangers too, taught me what real attention is about. Attention without feeling, I began to learn, is only a report. An openness — an empathy — was necessary if the attention was to matter.”

This quote, like so much of Oliver’s poetry, speaks to how attention—to nature, to our friends, and to our loved ones—can be a balm for the stresses of simply being alive. It emphasizes the importance of the quality of the attention we give. I, like so many, am used to being fast-paced, always wanting to be productive. I can see the flower growing in my lawn without ever noticing the miracle of its growth in the first place. Mary Oliver has taught me to be open to the world, to be patient with it, to allow empathy into the way I approach all things. Moreover, her writing has helped me clarify what kind of life I strive to live, one of compassion, gratitude, and a deep connection and appreciation for the people and things that surround me.

The poem “The Summer Day” is well known for its final lines: “tell me, what is it you plan to do/ with your one wild and precious life?” but I invite us to take a closer look at earlier lines:

“I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I’ve been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?”

Her answer to that very question is shown here: she plans to pay attention, to be idle. She plans to allow herself to simply exist.

Attention today is a commodity. We have so much to pay attention to that it is easy to exist in constant overwhelm. But Oliver tells us that there is time to pay attention. There is so much importance in allowing ourselves to cool off, to observe, and to appreciate. That even while the country seems to be falling apart before our eyes, the sunset tonight was absolutely gorgeous. The horrors persist, but so do the dandelions! I do not know how to fix everything, but I know how to stand underneath the temporality of lilac blossoms and thank them. I have to monitor the intake of news I consume, but this bee has just reminded me of the interconnectedness of all things. Small joys are still joys, and not only are we allowed to enjoy them, we must. The last line of Oliver’s poem “Don’t Hesitate” is a simple reminder: “Joy is not made to be a crumb.” Our time spent in the presence of the wild violets in a patch of grass will not systematically solve anything, true. But allowing ourselves to notice the breathtaking beauty of the world provides nourishment that can extend beyond the self, rippling through the planet and the precious life upon it.

As Oliver says in her poem, “Yes! No!,” “To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work.”

To Read More Mary Oliver, Check out: