“We’re sold that the finish line lies yonder,

just out of reach. Just beyond the bay.

It sits and waits for us as we pull our American dreams with us

—tied to our ankles, but presented as Mercury’s wings.” —Final stanza of a poem by Bond & Grace’s Creative Director, Maggie Lemak

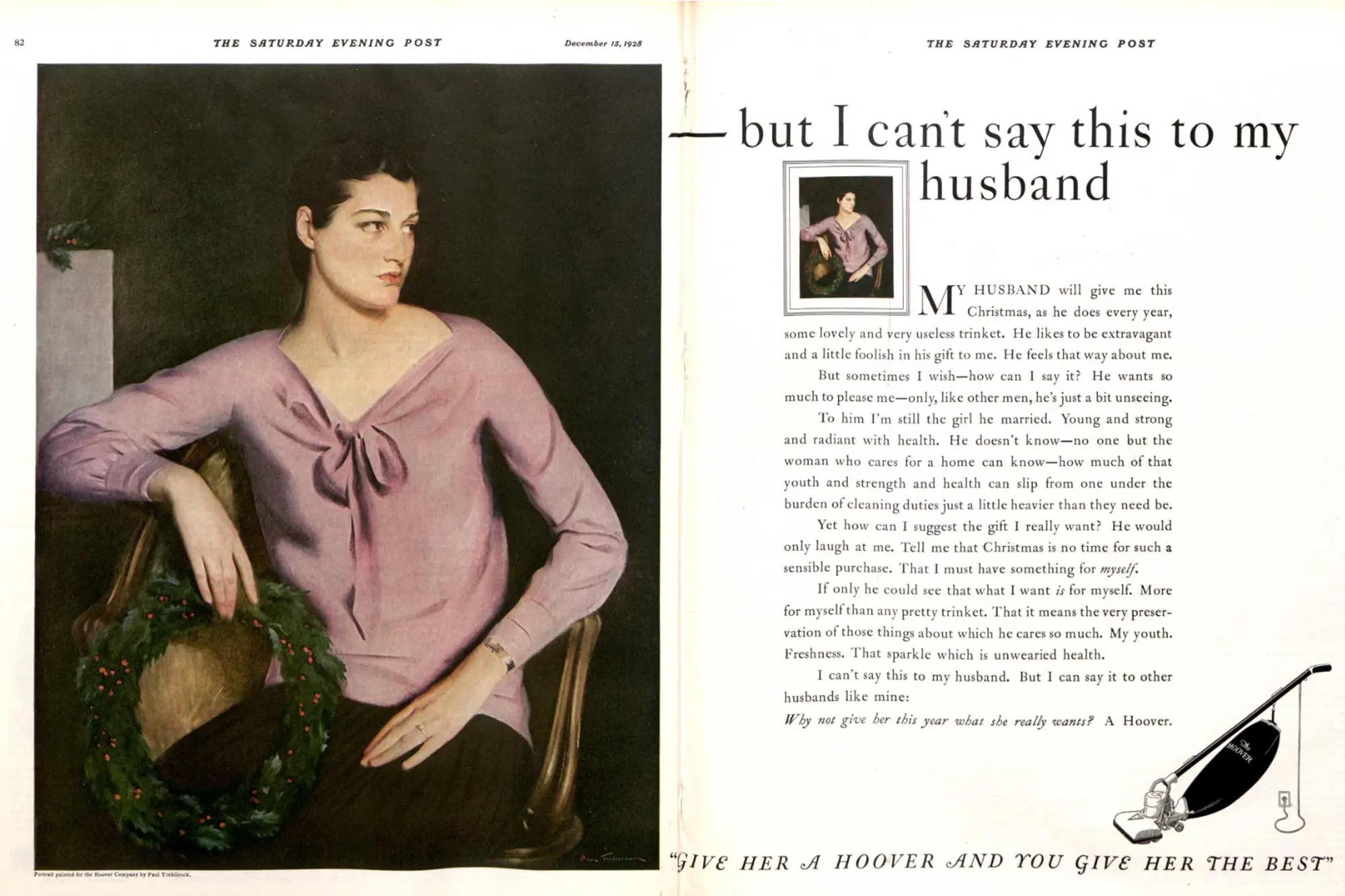

Last fall, when our award-winning creative team first set out to determine what each page of The Great Gatsby Art Novel should look like, there was one non-negotiable. The rise of modern advertising and the surge in 1920s consumerism should be palpable in its design—sleek and minimalist, the Art Novel should glisten with allure, like the pages of a glossy magazine.

A century later, we Americans are well accustomed to the idea that advertising packages perfection, blatantly conceals the truth, and frankly, makes us more anxious, needy, and insecure. Having worked briefly as a copywriter for a New York advertising firm before finding success as a novelist, F. Scott Fitzgerald had a unique lens into the industry and became a strong critic of it, writing later in life to his daughter Scottie, “Advertising is a racket, like the movies and the brokerage business. You cannot be honest without admitting that its constructive contribution to humanity is exactly minus zero.”

With its cutting critique of the upper class, and that famous scene where Daisy sobs hysterically at how beautiful Gatsby’s silk shirts are, The Great Gatsby reflects Fitzgerald’s attitude toward consumer culture. The most haunting and obvious example in the novel can be found in Doctor T.J. Eckleburg—that infamous billboard featuring omniscient eyes with “retinas one yard high”—who serves as a silent reminder of the hollowness of capitalism and the underclass imperiled in its wake.

While the symbolism behind the billboard may seem quaint to today’s readers in our world of AI and ad overload, Fitzgerald’s poignant critique of consumerism and the shallowness of material desire in Gatsby was far from entrenched in the minds of its readers. Though print advertising had existed since the late nineteenth century, it was in the 1920s that it exploded alongside the rise of radio commercials which echoed through American living rooms by the middle of the decade.

A newly emboldened advertising industry capitalized on the changing societal attitudes of American men and women whose daily lives and values were shifting in the wake of war. Disillusioned by the horrors and casualties of WWI yet buoyed financially by a booming stock market, many middle-class Americans found themselves caught between two competing forces: newfound wealth and lingering sadness. As the perfect conditions for spending took root, so too did the invention of marketing aspiration and social ascent through must-have consumer products. Never before had women been so boldly depicted driving cars, had the bodily functions of their underarms been publicly addressed, or had feminine hygiene been the supposed catalyst for broken marriages.

Until, that is, the ad industry got savvy and hired copywriters, psychologists, and behavioral scientists to probe, pinpoint, and analyze their ideal audience with the exactitude of a magnifying glass: white middle-class women. Emboldened by the ratification of the 19th Amendment and newly responsible for household-related purchases, women were seen as emotionally vulnerable and thus susceptible to advertising—or as one industry leader put it, a group in possession of “well-authenticated greater emotionality [than men]” and a “natural inferiority complex.” By 1929, ad spending had swelled from $700 million in 1914 to nearly $3 billion, as companies marketed their products to be “magical carpets” offering quick fixes for self and lifestyle improvement.

In Gatsby, Tom’s mistress Myrtle Wilson is the prime example of this emotionally insecure, wealth-envying trope of a woman who has been swept off her feet by material desire. Becoming utterly distressed by her “to do” list of purchases, she cries, “I’m going to make a list of all the things I’ve got to get. A massage and a wave, and a collar for the dog, and one of those cute little ashtrays where you touch a spring, and a wreath with a black silk bow for Mother’s grave that’ll last all summer.”

This breathless list, ridiculous yet so very human, shows just how powerful the illusion of consumer fulfillment had become. But it wasn’t just fictional women who believed a new ashtray or silk ribbon might transform their lives; real women, too, were being sold this fantasy in magazines and on the radio.

Take a 1928 Chevrolet ad for example. The very concept of women’s liberation became entwined with material culture, such that possessing certain goods became equated—in the minds of white American women—with their developing notions of autonomy and the newfound ability to choose. “The time has now come when ‘a car for her, too’ is a necessity,” the Chevrolet ad boasts, positioning the new model as “gentle,” and easily controlled by even the “most timid [female] driver.”

But such sexist language seems harmless in comparison to what Lysol was cooking up behind closed doors. A campaign launched in the late 1920s suggested that women’s intimate relationships were not only at stake but teetering on the brink of collapse, should women fail to maintain “complete” feminine hygiene. “Complete,” in this case, meant douching with the poisonous disinfectant. “Instead of blaming him if married love begins to cool, she should question herself,” the Lysol ad reads. Buckle up, ladies, it’s going to be painful! According to scholar and professor Lisa Wade, this campaign was in fact intended to encourage the use of the disinfectant as birth control, despite there already being 193 Lysol poisonings on the record by 1911, and as many as five deaths from its use, according to Mother Jones.

Beyond concerns of feminine hygiene, slimness was a requisite for landing a husband and keeping him. Lucky Strike cigarettes launched their famous “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet” campaign in 1928, explicitly targeting women’s desire to stay thin. The campaign worked; Lucky Strike’s market share soared soon thereafter, making it the most popular cigarette brand in the U.S. by the early 1930s.

The list of misogynistic, tongue-in-cheek advertisements pegged to pseudo-scientific claims goes on and on; antiperspirant deodorant as the antidote to women’s “nervousness” and the absolutely essential solve for “fastidious women who want to be absolutely sure of their daintiness”; Listerine marketed as the remedy for “halitosis,” a previously unheard-of medical condition cleverly invented to sell the oh-so-minty mouthwash; and Odo-ro-no toilet water, a strangely-named, scented liquid that not only removed stains but “corrects excessive perspiration” with only “three applications a week.”

So prescient was Fitzgerald’s take on the false promises consumerism sold—including Rolls-Royces so clean their windshields “mirrored a dozen suns,” as he described Gatsby’s—that the Federal Trade Commission, America’s new government agency overseeing ethics in advertising, began to take notice. In 1927, the FTC filed a significant false advertising case against a product called McGowan’s Reducine, a weight-loss drug that claimed it could make body fat “dissolve” into thin air, “leaving the figure slim and properly rounded, giving the lithe grace to the body every man and woman desires.”

With all of this rich, and rather unsettling history of the birth of modern American advertising and consumerism in mind, all of the glitz and glamour echoing through Jay Gatsby’s arched hallways and gilded personal histories should be read differently—and be taken with a grain of salt. There’s an undercurrent of sadness in it all, a stark, uneasy warning about what lies beneath the freshly cut lawns, well-tailored suits, and “monstrous” luxury vehicles. Let us recall the ash-grey men who labor in the Valley of Ashes through the day and night just down the highway from Gatsby’s guests who whisper to their husbands in king beds, God, wasn’t his Rolls-Royce beautiful? Like Gatsby’s parties, advertising distracts the well-heeled—and all of us who try to look the part—from the true inequities of America.

With the 1% now ruling our country, it’s safe to say we have all fallen prey to capitalism's conniving ways. We are made to believe that we need whatever is being sold—faster than our society needs reform, sooner than our neighbor needs a hot meal, and quicker than even Amazon Prime could have it delivered. Fitzgerald’s sharp, cynical tale of American longing should come as a much-needed reminder that the American Dream is a state of mind rooted in unity, equality, and achievement—a promise to ourselves and to each other that can’t be bought or sold.

Further Reading and Sources

- The 1920s: “Sell Them Their Dreams”, VSMD.com

- Early Radio and Advertisements, New York: A Documentary Film, PBS

- Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernism, Roland Marchand

- “The Golden Age of Advertising,” American Heritage