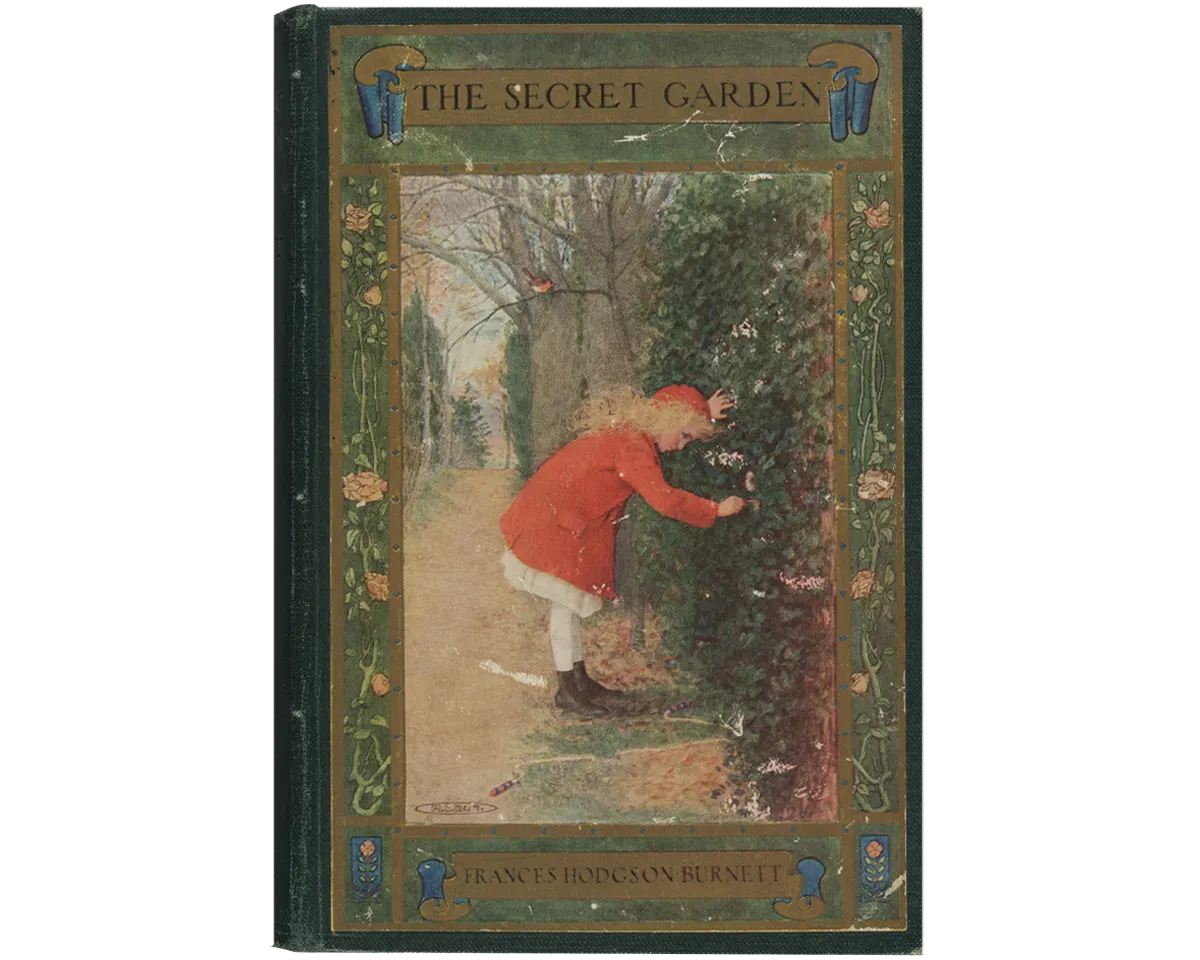

I don’t remember when I first read The Secret Garden as a child; I have lost count of the number of times I have re-read it over the decades since. But I know the story took glad hold of my imagination the moment I first stepped through that hidden door in the garden wall with Mary Lennox.

Of course, my imagination was predisposed to hear the bells that Frances Hodgson Burnett was ringing. Classic fairy tales like “Rapunzel,” and “Beauty and the Beast” held all The Secret Garden’s enchanting tropes of forbidden gardens, illicit entry, lonely children who both receive and become agents of magical transformation and healing.

However, the real roots of The Secret Garden go far deeper than fairy tales, though it’s unclear that Frances Hodgson Burnett was consciously aware of it. Whether she knew it or not, however, that Yorkshire garden was firmly planted in thousands of years of the rich soil of mythic imagination and literature, in holy texts and gardens both mythical and real. Enclosed “secret” gardens have been sacred places of peace, safety, beauty, refreshment, and healing all over the world for millennia.

When Alexander the Great conquered the Persian empire in 330 BCE, he was so impressed by the beauty and order of the 6th-century BCE King Cyrus’ enclosed gardens that he replicated them when he went to Rome. Through Moorish influence, Persian garden design also made its way to Spain.

Especially in Christian medieval and Renaissance literature, the rich complex symbolism of an enclosed garden really took root. The whole sweep of salvation history begins and ends, for Christians, in a garden. In the Garden of Eden, God placed the first humans, and planted the Tree of Life—a garden brimming with every kind of living thing, but also with the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The possibility of temptation and sin were there from the beginning.

From Creation, to Adam and Eve’s banishment from the Garden, to the redemption of human history in Jesus’ agony in the Garden of Gethsemane and his victory over death in the Garden of the Resurrection, the narrative arc is clear. A garden is created; it is lost—or abandoned, or neglected or damaged in some way. It is restored. And it always points toward the everlasting garden of Paradise.

These tropes of creation, loss, and restoration—all as a foretaste of heaven—figure in literary gardens from the 13th-century allegorical Roman de la Rose to Spenser’s 16th-century Faerie Queen to Milton’s 17th-century Paradise Lost. And this same trajectory—complete with Colin’s joyful conviction that, thanks to the gardens’ magic healing power, he is going “to live forever” (Chapter 20)—is present in The Secret Garden and in fact shapes the entire story.

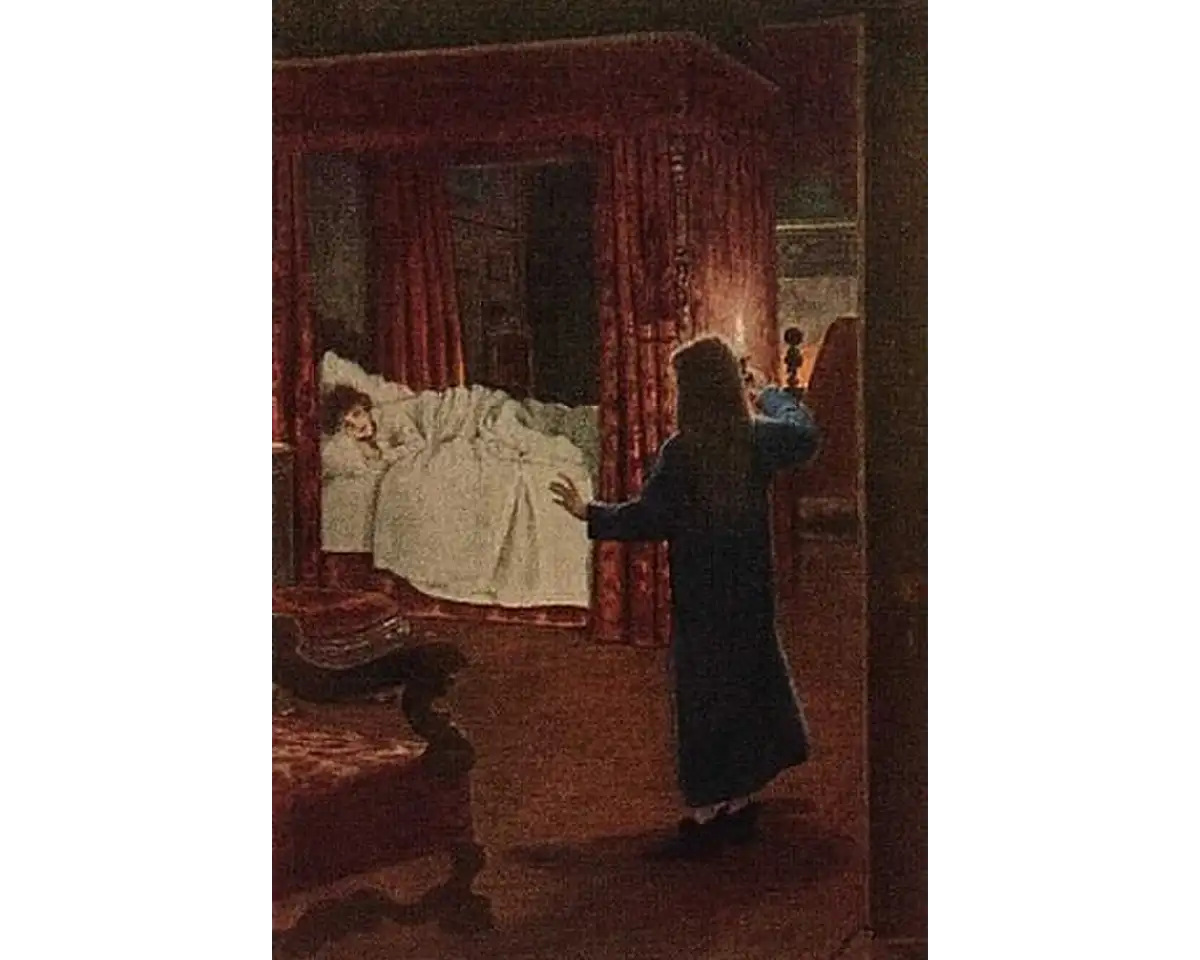

As readers of Frances Hodgson Burnett know, Archibald Craven created a special private garden for his bride Lilias. The young couple spent many happy hours alone in the garden, reading, talking, and tending the roses: she liked to sit on a low bench-like branch of a tree there that was covered with climbing roses. One day, when she was pregnant, sitting on the branch, it broke beneath her. Lilias, badly injured in the fall, died the next day, after giving birth to Colin. (Chapter 5)

This was indeed a fall from grace: the fairy tale garden became a garden of loss. In his extreme grief, Mr. Craven could not bring himself to love—or even to look at—the motherless infant. He locks the garden, burying the key and forbidding anyone to enter it, or speak of it.

Interestingly, that fateful tree, when the children discover the secret garden 10 years later, is described as “very old and gray, covered with gray lichen” but not as dead. Dickon used his pocketknife to cut carefully into the bark of the neglected trees and finds most of them are green inside: alive. And roses will once again cover the tree, including the broken branch.

This mystery of hidden, secret life deep down things, is scriptural as well. There is “hope for a tree” even “if it is cut down, [that] it will sprout again… Its roots may grow old in the ground yet at the scent of water it will bud and put forth shoots.” (Job 14:7-9)

Which brings us to one of the loveliest parts of the Secret Garden: the Magic that runs through it.

Burnett sought consolation for the tragic death of her young son in the metaphysical ideas popular at the time. “New Thought” emphasized the power of positive thinking, and the healing power of nature for all kinds of physical and emotional afflictions.

As Colin stops feeling sorry for himself and begins to take an interest in Mary’s stories about the “secret garden” that she has found and that she and Dickon are beginning to restore, he begins to get well, to gain strength and health.

Both he and Mary attribute this to magic, the Magic of the garden. and Colin becomes evangelical in his enthusiasm. “Magic is all around us, everything is made out of it,” he declares. “There is magic in everything.”

This belief in the healing “magic” of the garden, as it comes back to life after a decade of neglect, also (and again, perhaps unconsciously) reflects profound insights from poets and Christian mystics.

The English Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins believed in an enduring “freshness deep down things,” the indefatigable instinct for life that the Book of Job describes as reviving “at the scent of water.” Hildegard of Bingen, 12th-century abbess and mystic, had a vision of what she called viriditas, the mysterious divine life force that animates all of Creation. Hildegard believed that this was nothing other than “the greening power of God,” the love of the Creator for all Creation, for all living things.

This greening power is not just of nature, it is of God.

In any event, let’s not quibble. As Colin himself admits, “I don’t know its name, so I call it Magic.”

Colin asks Dickon’s mother if she believes in Magic, and she responds generously: “That I do, lad. I never knowed it by that name, but what does the name matter? …It’s the Good Big Thing, the Joy Maker.”

Ben Weatherby, the gardener, suggests when Colin, well and strong again, exclaims that he “feels as if he wants to shout out something thankful, joyful,” that he might express his gratitude by singing the Doxology (Chapter 26). Colin had never heard of it, never having been to church in his invalid life. Dickon sings it for him: “Praise God from whom all blessings flow; praise God, all creatures here below.” That seems just right to Colin, who immediately declares “I want to sing it too; it’s my song.”

“Perhaps,” he muses, “God and Magic are the same thing. How can we know the exact names of everything?”

The really wonderful thing about the Magic, whatever we call it, is that it is firmly connected with the mothers in the story. Not just the ample maternal affection of Dickon’s mother, but the spirit of young Lilias herself, and her undying love for her husband and son, direct the Magic.

Colin, in his exuberant delight in his own returning strength, hugs Mrs. Sowerby and exclaims, “I wish you were my mother.” She responds, “Thy own mother’s in this ‘ere very garden. She couldna keep out of it.”

And Lilias speaks to Mr. Craven in a dream, when he is far from home, sweetly calling his name. “Where are you?” he asks. “In the garden, in the garden!” answers the voice of his beloved. He returns home from his long exile, feeling “alive again.” (Chapter 27). Colin had the portrait of his mother, which hangs in his room, covered with a curtain because her laughing face made him feel angry and miserable. When he is well again, the curtain is removed because now he “likes to look at her….I think she must have been a sort of Magic person.”

Everyone in the book who has been ill and miserable is healed and transformed: Mary, Colin, even Mr. Craven. And relationships are restored: father and son, after a lifetime of estrangement, are reunited in the garden, brought together by Magic that is real and strong and powerful, whatever we call it.

C.S. Lewis would call it not just “deep magic” but the “deeper magic” (of which the evil witch in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe knows nothing). The deeper magic from before the dawn of time is all about the death-defeating power of sacrificial love—even though Colin’s mother died at his birth, she is alive in the garden, in her undying love for both father and son.

And that is perhaps the real Magic in the Garden after all.

Deborah Smith Douglas has been an avid reader all her life. She has also been a lawyer, a writer and editor, an operator of both a drill press and a switchboard, a wife and mother, a really bad skier, and a worse poker player. She is the author of two and a half books, more about all of which can be found at deborahsmithdouglas.com.