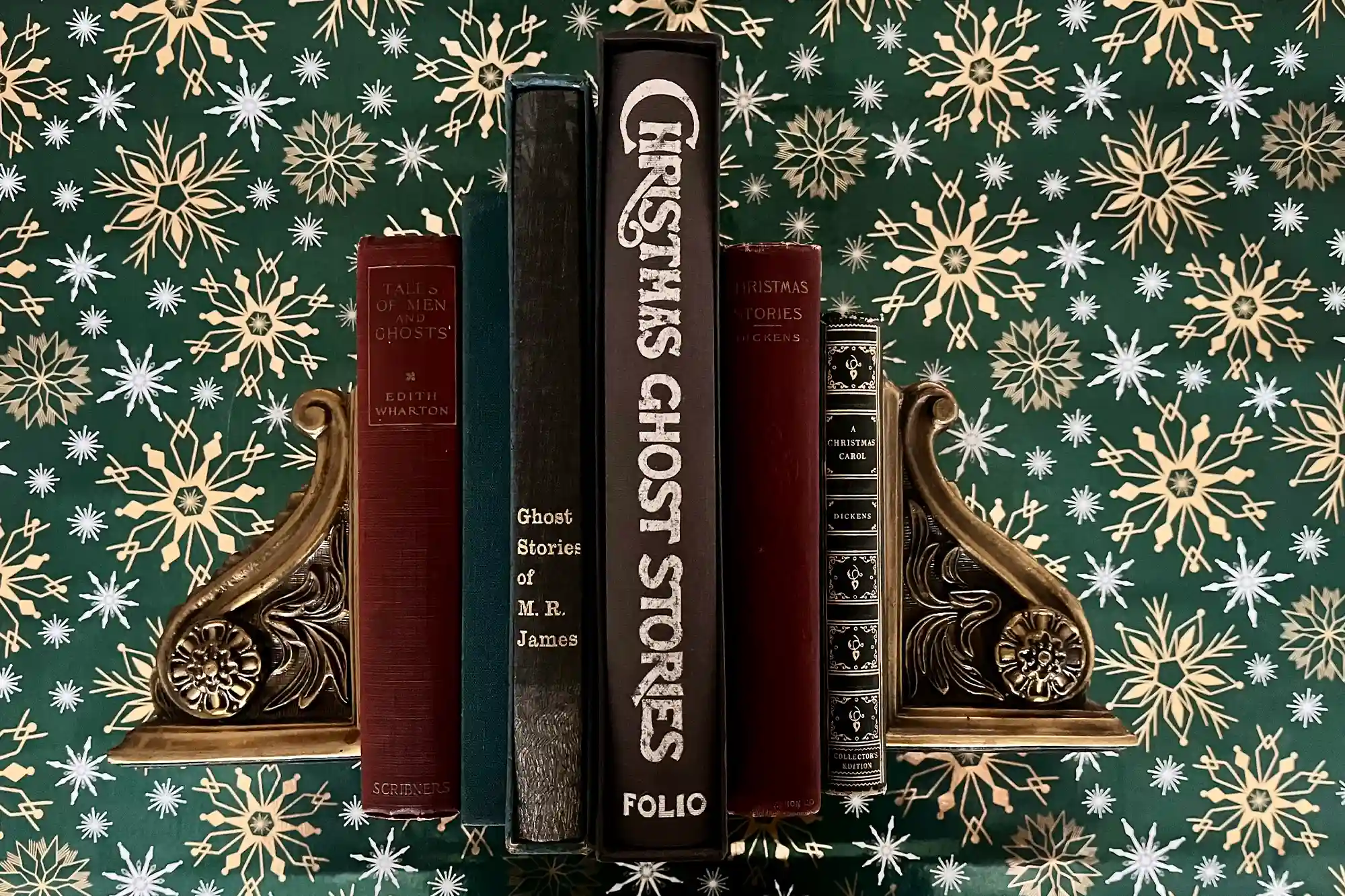

Ghost stories have always belonged to the Holiday Season.

Not purely because winter, and dying, can be frightening, but because shelter makes us feel safe. Because the presence of our loved ones, the warmth of our homes, the glow of fires makes us feel held enough to explore regret, to process loss, and to consider the unknown. Christmas has long been a moment that lends itself to looking inward, or backward, to take inventory of what we’ve kept and what we’ve lost.

The Victorians understood this. As industrialization rearranged family life and scientific certainty began to eclipse religious mystery, ghost stories emerged not as cheap thrills but as moral reckonings. They insisted that the past mattered. That love lingered. That progress did not erase responsibility or consequence. Dickens didn’t only give us ghosts to terrify us; he gave us ghosts to remind us what was still worth having and what was worth saving.

Occasionally my family had a fire to gather around, but mostly we rented VHS tapes and the glow came from our modest yet gigantically heavy TV. But the ritual hadn’t disappeared. It had been reimagined.

So yes, in recent decades, we’ve gathered around screens, but I do love the return to form of a good Holiday movie watch. We return, year after year, to the same movies not only out of nostalgia, but because they perform the same work ghost stories always have. They let us contrast fear and sorrow with the safety of soft blankets and a beloved setting. This year, when trying to figure out how and where to stream my favorites, I found myself wondering, what ghosts are at the heart of each Holiday classic?

In It’s a Wonderful Life we meet the ghost of the life not lived. George Bailey is haunted not by failure, but by the possibility that his sacrifices amounted to nothing. The fear in the film is not Clarence’s wings or the alternate universe, it’s the quiet suspicion that usefulness goes unnoticed while it’s happening. The comfort the ghost leads us to comes when George realizes that meaning rarely announces itself as destiny as life is being lived. It can seem quiet and small from the inside but meaning accumulates slowly, near invisibly, like falling snow.

Die Hard gives us the ghost of Reagan-era male usefulness. John McClane is a man whose value was once defined by decisiveness, physical competence, and being needed. Now he fears that the world has moved on without him. The skyscraper is not just a battleground; it’s a corporate maze where systems have begun to replace individuals. McClane is fighting terrorists, which is, of course, riveting, but he might also be fighting irrelevance. The hope, by the end, is not victory but reunion, the restoration of a home where he still matters.

I think Home Alone is the ghost of growing up. Kevin begins the film drunk on the fantasy of adulthood: independence, control, freedom from family chaos. But Christmas strips that fantasy bare. The house grows too large. The nights are too quiet. The joy of being left alone lasts exactly as long as it takes to realize no one is coming back yet. Like so many ghost stories, the danger is the intruder, the horror is the absence of protection. Our holiday relief comes from clever traps, yes, but more deeply from the return of family, imperfect and loud and necessary.

Finally, A Charlie Brown Christmas is the ghost of meaning itself. Charlie Brown is haunted by the fear that everything sacred has been hollowed out, reduced to spectacle, consumption, noise. What makes the film quietly radical is its refusal to inflate the answer. Meaning, it suggests, is small. It lives in simplicity, shared presence, and a tree that looks like it shouldn’t survive but somehow does.

So yes, indulge in your nostalgia this year if you like, but maybe call it ritual?

We return to these movies because we already know the ending. We know the family will come back. We know the house will be warm again. That foreknowledge is not a failure of imagination, it’s a gift. It allows us to confront difficult truths without fear of being undone by them.

Victorian ghost stories offered the same mercy. They acknowledged disruption while insisting on repair. They reminded readers that progress need not mean severance, and that home remained a place you could return to even if changed.

Maybe the real ghost at the Holidays is time. I’d love to lay on my family room floor again and have the whole crew watch a rented VHS.

These stories—these familiar hauntings—are how we invite the ghost back in once a year, on our own terms. We let it show us what we might someday lose, what we’ve been lucky enough to have, and take time next to the fire to be grateful for what still matters.