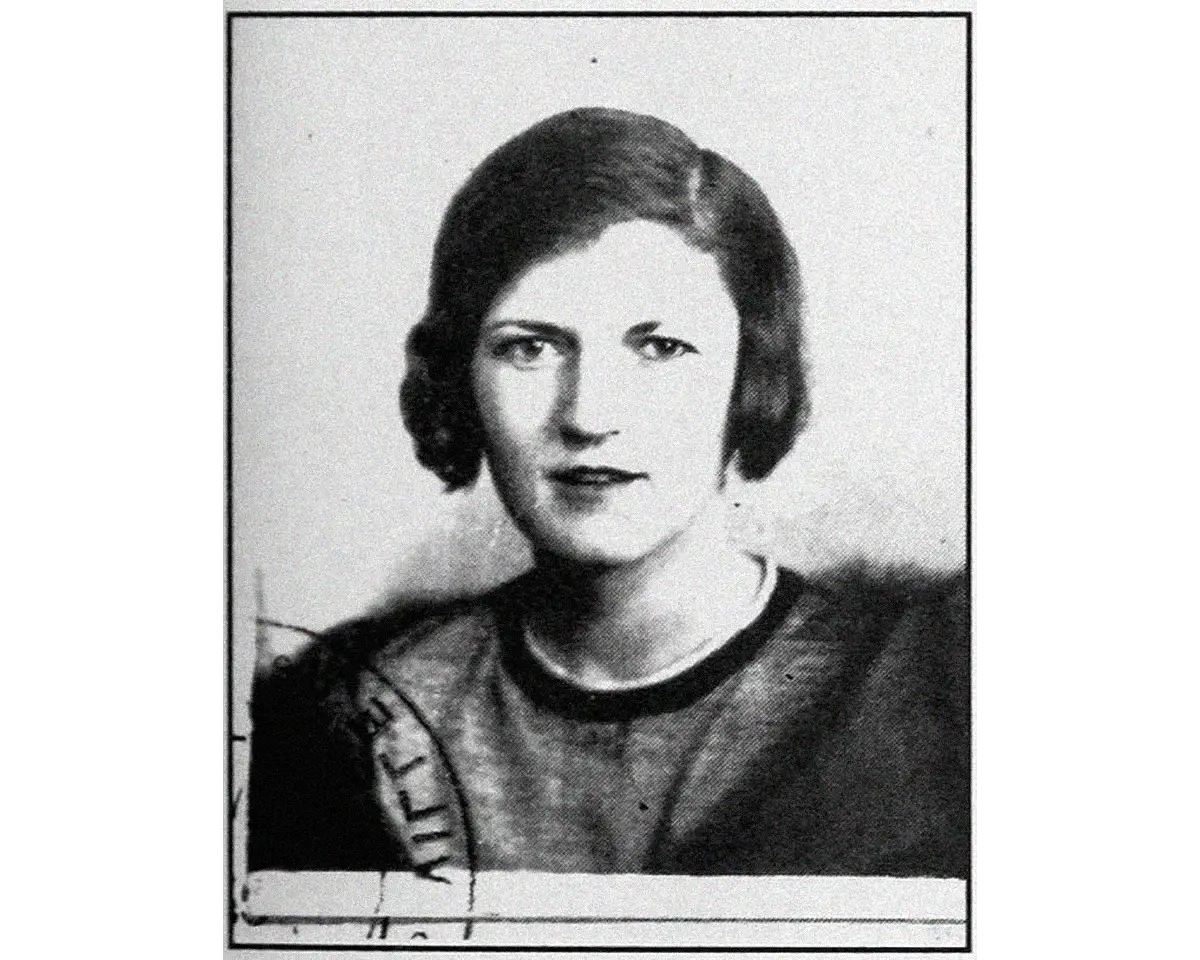

When it comes to literary power couples, few people have left as lasting a legacy as the Fitzgeralds. In addition to Scott’s prolific writing, the pair lived a famously tragic and compelling life. During their wild, youthful days in New York, writer Ring Lardner called Scott and Zelda “the prince and princess of their generation.” They dressed beautifully, behaved wildly, were constantly written up in the papers, and embodied the rip-roaring 1920s. As they grew older, Scott’s alcoholism and Zelda’s mental illness led to violent and public fights, illicit affairs, and the tragic disillusionment of their marriage. To this day, the couple retains a kind of cult following, a legacy of triumph and turmoil that is quintessentially American.

.webp)

This fraught and troubled dynamic bled into their literary lives as well. And while Scott’s work has been well-studied in the years since World War II, Zelda’s has largely gone unexamined, with many people not knowing that she, too, was a writer. In recent years, however, a new narrative has begun to emerge. One in which Zelda, like so many forgotten wives of the famous, was silenced and even plagiarized by her husband. This narrative, while not entirely untrue, vastly oversimplifies Scott and Zelda’s relationship. It paints her as the passive victim to his controlling monster. Ultimately, it does a disservice to both parties, who were mutually creative, artistic, and troubled. To get to the heart of the matter, we’ll break down Scott and Zelda’s life and work: the passion and the plagiarism, to better understand this remarkable couple.

.webp)

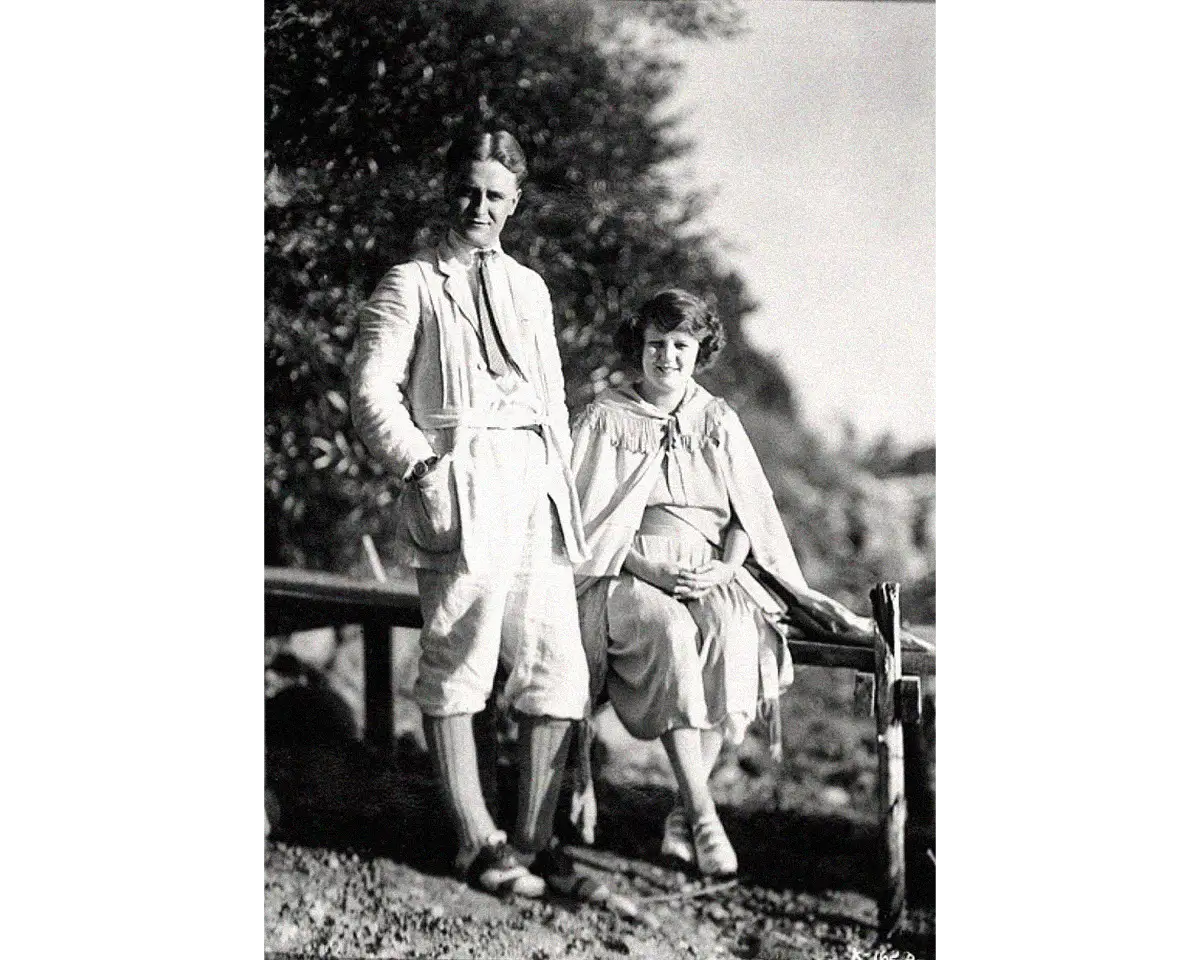

Scott and Zelda first met in 1917. Scott had enlisted in the U.S. Army, eager to serve in World War I, which was shaping up to be the defining geopolitical conflict of his generation. Much to his disappointment, he was never sent abroad and was instead stationed at Camp Sheridan near Montgomery, Alabama, where he met the Southern belle Zelda Sayre, the wealthy daughter of an Alabama Supreme Court Justice. Captivated by her physical beauty and ferocious spirit, Fitzgerald later wrote that he “fell in love with her courage, her sincerity and her flaming self-respect.”

During his time in the army, Scott wrote his first novel, The Romantic Egoist, which was later published as This Side of Paradise (1920). He submitted a draft of the novel for publication at Charles Scribner’s Sons but was rejected. It is apparent from Zelda’s letters to Scott during this time just how much she loved him, but she also harbored legitimate concerns about his ability to provide for her. Compounding Scott’s disappointment, she ended their three-month engagement. Heartbroken, Scott moved back home to Saint Paul, Minnesota, where he revised the novel in his parents’ attic until it was accepted by Scribner’s in 1920. He wrote to Zelda of his success, and the couple picked up where they left off, getting married only a week after the novel’s publication.

From this first foundational text, Scott’s reliance on Zelda as a literary muse is apparent. This novel also contains his most flagrant act of plagiarism. In April 1919, Zelda wrote a letter to Scott musing on the romantic nature of the Confederate graveyards in her hometown of Montgomery. She writes:

“I can’t find anything hopeless in having lived—All the broken columns and clasped hands and doves and angels mean romances—and in a hundred years I think I shall like having young people speculate on whether my eyes were brown or blue—of course, they are neither—I hope my grave has an air of many, many years ago about it—Isn’t it funny how, out of a row of Confederate soldiers, two or three will make you think of dead lovers and dead loves—when they’re exactly like the others, even to the yellowish moss? Old death is so beautiful—so very beautiful—we will die together—I know—Sweetheart.”

Now consider this closing passage from This Side of Paradise:

“He wondered that graves ever made people consider life in vain. Somehow, he could find nothing hopeless in having lived. All the broken columns and clasped hands and doves and angels meant romance. He fancied that in a hundred years he would like having young people speculate as to whether his eyes were brown or blue, and he hoped quite passionately that his grave would have about it an air of many, many years ago. It seemed strange that out of a row of Union soldiers two or three would make him think of dead loves and dead lovers, when they were exactly like the rest, even to the yellowish moss.”

This Side of Paradise was a runaway hit, and in 1922 Scott published his second novel, The Beautiful and Damned. After its release, Scott asked Zelda to write a review of the novel in The New York Tribune. The idea was to play into the public’s fascination with the couple to boost book sales; Zelda, never one to pass up an opportunity to showcase her wit and humor, took it up with zeal. Zelda leans into the public perception of her as a ditzy beauty, saying that this was her first time reading the novel, even though she reviewed the manuscript multiple times. She then urges readers to buy the book so that she can purchase “the cutest cloth of gold dress for only $300 in a store on Forty-second Street.” The largely satirical article contains kernels of truth, however, and perhaps insights into how she might have felt about Scott lifting her writing. She wrote:

.webp)

“It seems to me that on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and, also, scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald (I believe that is how he spells his name) seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

In the early 1920s, Scott set to work on his masterpiece, The Great Gatsby. He considered his earlier novels to be works of pop culture and wanted to create something lasting and transcendent. And while he no doubt succeeded in that mission, he also relied on old habits. Daisy’s iconic line spoken at the birth of her daughter: “I’m glad it’s a girl. And I hope she’ll be a fool—that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool.” is strikingly similar to a comment Zelda said upon the birth of the couple’s daughter, Scottie: “I hope it’s beautiful and a fool—a beautiful little fool.”

It is worth mentioning that Scottie herself would later defend her father and attest to the many ways in which he encouraged and supported Zelda’s creative life, from her writing to her painting to her dance. In the foreword to an exhibition catalog for her mother’s artwork, Scottie wrote that her father “greatly appreciated and encouraged his wife’s unusual talents and ebullient imagination. Not only did he arrange for the first showing of her paintings in New York in 1934, he sat through long hours of rehearsals for her play, Scandalabra, staged by a little theatre group in Baltimore; he spent many hours editing the short stories she sold to College Humor and to Scribner’s magazine; and though I was too young to remember clearly, I feel quite sure that he was even in favor of her ballet lessons.”

Zelda loyalists will often point to a series of short stories she wrote in the late 1920s that were published under Scott’s name as the coup de grâce of his betrayal, but this, too, is an oversimplification. Zelda knew that Scott’s stories went for a small fortune, and she would get paid substantially more if they were published under his name. Additionally, this money was entirely her own and went largely towards her ballet lessons, a passion that was teetering dangerously close to obsession.

.webp)

In the late 1920s, Zelda and Scott’s marriage had become increasingly fraught. He was drinking more, and she was spending all her time with her ballet tutor, the Russian dancer Lubov Egorova. In September 1929, while driving through France with Scott and Scottie, Zelda attempted to grab the wheel and drive the family off a cliff. In April 1930, anxious about being late to a ballet lesson, she jumped out of the car into the middle of traffic and began running to the studio. By the end of April, she had completely broken down and was shortly after diagnosed with schizophrenia and institutionalized in Switzerland.

Zelda’s institutionalization impacted the couple in distinct and adverse ways. It put Scott—who was determined to get her the best care possible—under incredible financial pressure. The pair had never been good with money, and Zelda’s treatment, paired with the cost of Scottie’s education, had Scott completely underwater. To pay his accumulating debts, he put off his hopes of writing another novel in favor of well-paying short stories he could churn out quickly. The stress compounded his drinking, and he would drink and write to the point of exhaustion and illness.

.webp)

For Zelda, a woman who had always lived with fierce passion and independence, the claustrophobia and vigilance of the hospitals were devastating. In all her letters to Scott through the 1930s, the most recurring sentiment in her moments of lucidity is her desire for financial independence and freedom. She hated being a burden to her family and begged him to send her books to read and to pass along her short stories to editors.

Scott, while concerned that work would exacerbate her illness, was generally obliging. In 1930, he wrote to his editor at Scribner’s, Max Perkins, to pass along Zelda’s stories, saying they were beautifully written and had “a strange, haunting, and evocative quality that is absolutely new.” While the stories were never published, Zelda did begin work on a memoir disguised as a novel, Save Me the Waltz (1932).

Save Me the Waltz is where the cracks between Scott and Zelda post-institutionalization truly start to show. When he could, Scott had been alchemizing his marriage troubles, travels around Europe, and Zelda’s illness into a novel, Tender is the Night (1934). But between his financial obligations and bouts of sickness, the going was slow. Zelda, on the other hand, wrote her novel in six weeks and sent it directly to Perkins, bypassing Scott.

Scott was deeply wounded by Zelda’s book, and feared that its shared material would make his novel unpublishable. He had shown some of his early chapters to Zelda and felt she had plagiarized him. In his mind, he had put himself under considerable financial hardship caring for her, only for her to go behind his back. To Zelda, this novel was a desperate attempt to alleviate some of that very financial hardship. She desperately wanted to tell her own story and, understandably, didn’t want to subject it to her husband’s (often heavy) editorial hand.

Critics cite Scott’s demands that Zelda cut their novels' shared material—which she reluctantly did— as an example of his cruel and controlling nature. And while this is true, he also could have made Zelda’s book dead in the water, forbidding his own publisher from releasing her material, something he importantly did not do. While both were wounded by this period in their lives, it is less a matter of plagiarism and more a complex question over who owns shared lived experiences. Scott and Zelda were both artists who knew no other way to process the trauma they had experienced but to put it in art. No wonder they often butted heads over their creative expression.

While Scott and Zelda’s life together was deeply troubled, they also had an enormous amount of love and admiration for each other, both personally and professionally. They were mutually cruel, unkind, generous, and supportive. They also both produced some of the most lyrical, evocative, and moving work of the 20th century, something, unfortunately, only Scott has gotten credit for.

While the matter of plagiarism is as complex as the writers at the center of it, the best way to solve this inequity is to read the works themselves. Zelda’s writing and artwork can be accessed below.

Zelda Fitzgerald’s Little-Known Art

The Collected Writings of Zelda Fitzgerald

To Learn More, Check Out…

Meyers, Jeffrey, F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography, Harper Collins Publishers, 1994.

Fitzgerald, Scott, and Zelda, Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda: The Love Letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Scribner, 2002.

.webp)