As the story goes, it was a warm June day in Pennsylvania in 1776 when a widowed seamstress named Betsy Ross cut the first five-pointed star of the American flag in one single, fateful snip of her scissors. Moments earlier, the cobblestone streets outside of her cash-strapped upholstery store had been bustling with life when George Washington, trailed by Robert Morris, and George Ross—all prominent Revolutionary War figures—came a’knockin’.

“Miss Ross,” President Washington uttered softly (or something of the like), “it is said you are most accomplished with the needle.” Presenting the demure Betsy, only 24 years old, with a rough sketch of the flag they envisioned for the emerging nation, the meek but experienced seamstress took one look at the poorly rendered drawing and shook her head. “Why gentleman, a five-pointed star is neater, and far quicker to cut.” Grabbing her upholstery shears, her well-worn thimble, and a scrap of coarse wool, she sat right down to work. No privacy needed, not a moment to waste.

And so the very first American Flag was stiched—or so we are told—with its iconic 13 alternating red and blue stripes and five-pointed stars of the same number, the latter arranged neatly in a circle against a navy blue square of fabric. Thirteen original colonies, independent and woven into wool, foretelling the formation of the United States of America just a few months later.

Betsy Ross has since become a national figure, her likeness beautified in paintings and immortalized onto postage stamps, bobbleheads, and pincushions. After all, who wouldn’t cherish the idea that our nation’s first flagmaker was not only a woman but a widow? A noble heroine, an entrepreneur, the humble seamstress lives on in social studies books and schoolrooms. Very much still alive in the American imagination, Ross represents more than just patriotism; with her needle and thread, she symbolically stitched the states together, as if she singlehandedly brought the nation into being.

The tale of the first American flag is, in fact, little more than a popular legend, a product of the mythmaking so fundamental to American identity and national belonging. While the emotional appeal of Betsy’s story is apparent, historians have long questioned its truth.

Born as Elizabeth Griscom on January 1, 1752, the eighth of 17 children born to Quaker parents, Betsy Ross was indeed an upholstress during the Revolutionary War known for her deft ways with needle, scissors, thimble, and thread. But the notion that she cut the stars of the first American flag in a “single snip”—or that her shears ever came within a mile of the first American flag, for that matter—is much debated. It wasn’t until 1870, half a century after Ross’ death, that her grandson William Canby recalled a tale told to him by his elderly grandmother in a lengthy speech given to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Despite little evidence to support his claims, Canby’s old granny’s tales spread like wildfire, his family lore taken as truth.

Now, to understand why the nation was so quick to latch onto Canby’s story, we need to rewind the clock. In 1870, America was hungry for heroes. Still reeling from the Civil War as it faced the challenges of Reconstruction, the country was rebuilding not only its infrastructure but its own identity. The centennial of the Declaration of Independence was on the horizon, and what better way to unify the nation than a romanticized myth involving domesticity, femininity, and patriotism?

A symbol of unity and virtue, Ross’ story was exactly the kind of origin story the nation needed—one that centered a grieving yet patriotic woman who completed the task laid before her dutifully and without question. Whether calculated or not, Canby’s timing was impeccable: his speech came just one month after the ratification of the 15th Amendment granted Black men the right to vote, leaving white women outraged at their continued exclusion. In a horrendously racist appeal published in The New York Times in 1869, Susan B. Anthony called the amendment the “establishment of an aristocracy of sex,” one that “elevated the very last of the most ignorant and degraded classes of men to the position of master over the very first and most educated and elevated classes of women.”

As women campaigned for rights past the kitchen and to the polls, Ross embodied the docile, quiet woman the white male establishment depended upon. In short, Canby’s story resonated. Betsy, Canby recalled, in his speech, “drove a thriving trade, was notable, prudent and industrious, and never had any time to spend in street gaping or gossip, and was, consequently, very much respected by her neighbors.” The perfect woman. So judicious, so virginal, so devoted to her country, that historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich has likened the fictitious figure to the Virgin Mary. Framing Ross within 19th-century ideals of Christian womanhood, Ulrich casts Ross as the female counterpart to George Washington, a maternal, chaste figure whose virginal image helped “transform a fragment of personal and family history into a quasi-religious epiphany.”

Pictured right: The Annunciation, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1655–1660)

Supporting this perception of Ross as not only mythologized but sanctified, Ulrich points to the most famous painting of the legend, The Birth of Our Nation’s Flag by Charles Weisgerber. Holding the original flag draped upon her lap, Ross—and the flag—are lit by streams of light pouring in from a nearby window. George Washington, Robert Morris, and George Ross hover nearby in a triangular formation, bearing a striking resemblance to the composition typical of Annunciation scenes in Christian iconography.

If Weisgerber sought images of Ross as he embarked on his painting, he would have found none. A devoted Ross-adoree, this was no setback; Weisgerber crafted her likeness using photographs of female family members for inspiration. Creative liberties aside, Weisgerber clearly hit a nerve; it didn’t take long for his glorified portrayal to capture the hearts and minds of Americans. Merely a year after its creation, the painting was displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair, seen by millions as it became etched into the cultural memory. With what Ulrich calls “the flag-veneration movement” underway, ten states over the next ten years would pass laws making flag celebrations a regular part of public school life.

If Charles Weisgerber had any inkling of doubt about the veracity of the Betsy Ross story, history has erased them. The Birth of Our Nation’s Flag is merely one surviving remnant of Weisberger’s contribution to Ross’ legacy. Not only did he purchase Ross’ upholstery store in Philadelphia and dedicate his life to a woman who he clearly knew less about than he thought, but he also, named his son Vexildomus (“Vexil” for short), however bizarrely, meaning “flag house” in Latin. A proud patriot, a Ross devotee, Weisgerber, as it turns out, was also a marketing genius.

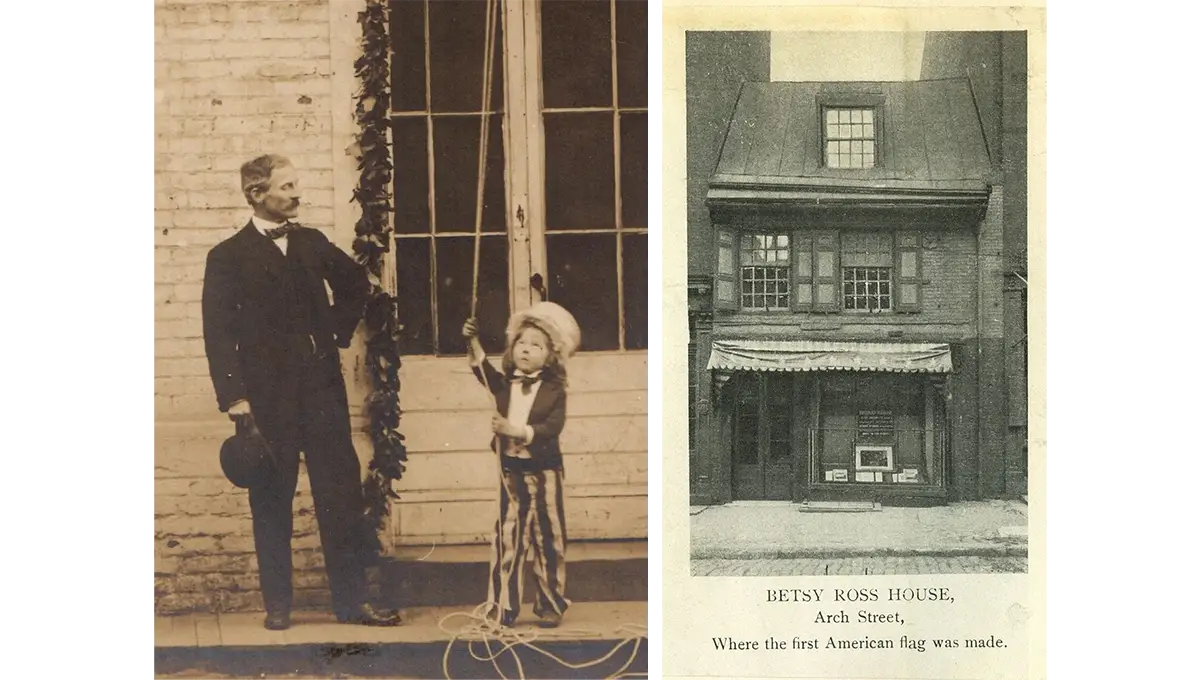

Weisgerber must have been beside himself after the attention his painting received from the World’s Fair; within five years he had moved into the upstairs floor of Ross’ old upholstery shop, co-founded the American Flag House and Betsy Ross Memorial Association, and began producing prints of his painting to fundraise for the historic home’s preservation. Apparently, by 1925, he had received donations from four million adults and their children across the country. Credited today with “saving” the Betsy Ross House from the threat of demolition, it is remiss of historians not to also credit Weisgerber as a marketing genius who had a financial incentive to further Ross’ cause.

With a quarter million visitors annually, the Betsy Ross House today remains a destination for starry-eyed visitors pining for the nostalgia-ridden era of national origin stories cobbled together from scraps of truth. Like the flag itself, Betsy Ross has become a symbol larger than life—one of the many American myths that is far easier to hold onto as truth than to unravel. Indeed, still today, Betsy Ross’ story fills a cultural craving: for a maternal founder, for patriotic simplicity, for a “prudent” heroine who loyally fulfilled her national duty while keeping her mouth shut. While the legend of the first American flag may not tell us much about what actually happened in 1776, it reveals a great deal about what America wanted to believe a century later—and perhaps still does.

Suggested Reading and Listening:

Broad Stripes, Bright Stars, and White Lies, Sidedoor Podcast, Season 7